A Player Cameo In Which Nintendo Game Remained Largely Unknown For Over A Decade? |

|

Think you know the answer? |

|

from How-To Geek https://ift.tt/2HaC36h

A Player Cameo In Which Nintendo Game Remained Largely Unknown For Over A Decade? |

|

Think you know the answer? |

|

Jeff Wise / OneZero:

Critics and parents question the ethics of using edutainment games like Prodigy, which has a freemium business model that relies on in-app purchases, in schools — Kids love “edutainment,” but does the business model exploit them? — erched on a rise overlooking the Hudson River …

Alison Griswold / Oversharing:

An analysis of data between August and December 2018 from Louisville, KY estimates that the average lifespan of shared scooters in the city was 28 days — CXLIV — Hello and welcome to Oversharing, a newsletter about the proverbial sharing economy. If you're returning from last week, thanks!

Janet Morrissey / New York Times:

A look at on-demand medical startups in the US like Heal and The I.V Doc, which are helping users get treatment for nonemergency problems at home or work — Businesses can deliver everything on demand, from dinner to dry cleaning. Some will even show up at your door to give you cupcakes or walk your dog.

Cade Metz / New York Times:

Sources: CEO of AI startup Clarifai says internal ethics officers do not suit small companies and that Clarifai would one day supply autonomous weapons — HALF MOON BAY, Calif. — When a news article revealed that Clarifai was working with the Pentagon and some employees questioned the ethics …

Kyle Wiggers / VentureBeat:

Ordr, a network-level cybersecurity platform which uses AI to flag suspicious events in real time, comes out of stealth and says it has raised $16.5M Series A — In this day and age, enterprises can't take a traditional IT approach to security — or so claims Ordr, a Santa Clara …

Jon Victor / The Information:

Source: Circle, which runs a cryptocurrency exchange Poloniex and which was reportedly valued at ~$3B last year after raising $246M, is raising another $250M — Circle, one of the biggest cryptocurrency startups in the U.S., is seeking to raise about $250 million in a combination of equity and debt …

This year’s Mobile World Congress — the CES for Android device makers — was awash with 5G handsets.

The world’s No.1 smartphone seller by marketshare, Samsung, got out ahead with a standalone launch event in San Francisco, showing off two 5G devices, just before fast-following Android rivals popped out their own 5G phones at launch events across Barcelona this week.

We’ve rounded up all these 5G handset launches here. Prices range from an eye-popping $2,600 for Huawei’s foldable phabet-to-tablet Mate X — and an equally eye-watering $1,980 for Samsung’s Galaxy Fold; another 5G handset that bends — to a rather more reasonable $680 for Xiaomi’s Mi Mix 3 5G, albeit the device is otherwise mid-tier. Other prices for 5G phones announced this week remain tbc.

Android OEMs are clearly hoping the hype around next-gen mobile networks can work a little marketing magic and kick-start stalled smartphone growth. Especially with reports suggesting Apple won’t launch a 5G iPhone until at least next year. So 5G is a space Android OEMs alone get to own for a while.

Chipmaker Qualcomm, which is embroiled in a bitter patent battle with Apple, was also on stage in Barcelona to support Xiaomi’s 5G phone launch — loudly claiming the next-gen tech is coming fast and will enhance “everything”.

“We like to work with companies like Xiaomi to take risks,” lavished Qualcomm’s president Cristiano Amon upon his hosts, using 5G uptake to jibe at Apple by implication. “When we look at the opportunity ahead of us for 5G we see an opportunity to create winners.”

Despite the heavy hype, Xiaomi’s on stage demo — which it claimed was the first live 5G video call outside China — seemed oddly staged and was not exactly lacking in latency.

“Real 5G — not fake 5G!” finished Donovan Sung, the Chinese OEM’s director of product management. As a 5G sales pitch it was all very underwhelming. Much more ‘so what’ than ‘must have’.

Whether 5G marketing hype alone will convince consumers it’s past time to upgrade seems highly unlikely.

Phones sell on features rather than connectivity per se, and — whatever Qualcomm claims — 5G is being soft-launched into the market by cash-constrained carriers whose boom times lie behind them, i.e. before over-the-top players had gobbled their messaging revenues and monopolized consumer eyeballs.

All of which makes 5G an incremental consumer upgrade proposition in the near to medium term.

Use-cases for the next-gen network tech, which is touted as able to support speeds up to 100x faster than LTE and deliver latency of just a few milliseconds (as well as connecting many more devices per cell site), are also still being formulated, let alone apps and services created to leverage 5G.

But selling a network upgrade to consumers by claiming the killer apps are going to be amazing but you just can’t show them any yet is as tough as trying to make theatre out of a marginally less janky video call.

“5G could potentially help [spark smartphone growth] in a couple of years as price points lower, and availability expands, but even that might not see growth rates similar to the transition to 3G and 4G,” suggests Carolina Milanesi, principal analyst at Creative Strategies, writing in a blog post discussing Samsung’s strategy with its latest device launches.

“This is not because 5G is not important, but because it is incremental when it comes to phones and it will be other devices that will deliver on experiences, we did not even think were possible. Consumers might end up, therefore, sharing their budget more than they did during the rise of smartphones.”

The ‘problem’ for 5G — if we can call it that — is that 4G/LTE networks are capably delivering all the stuff consumers love right now: Games, apps and video. Which means that for the vast majority of consumers there’s simply no reason to rush to shell out for a ‘5G-ready’ handset. Not if 5G is all the innovation it’s got going for it.

LG V50 ThinQ 5G with a dual screen accessory for gaming

Use cases such as better AR/VR are also a tough sell given how weak consumer demand has generally been on those fronts (with the odd branded exception).

The barebones reality is that commercial 5G networks are as rare as hen’s teeth right now, outside a few limited geographical locations in the U.S. and Asia. And 5G will remain a very patchy patchwork for the foreseeable future.

Indeed, it may take a very long time indeed to achieve nationwide coverage in many countries, if 5G even ends up stretching right to all those edges. (Alternative technologies do also exist which could help fill in gaps where the ROI just isn’t there for 5G.)

So again consumers buying phones with the puffed up idea of being able to tap into 5G right here, right now (Qualcomm claimed 2019 is going to be “the year of 5G!”) will find themselves limited to just a handful of urban locations around the world.

Analysts are clear that 5G rollouts, while coming, are going to be measured and targeted as carriers approach what’s touted as a multi-industry-transforming wireless technology cautiously, with an eye on their capex and while simultaneously trying to figure out how best to restructure their businesses to engage with all the partners they’ll need to forge business relations with, across industries, in order to successfully sell 5G’s transformative potential to all sorts of enterprises — and lock onto “the sweep spot where 5G makes sense”.

Enterprise rollouts therefore look likely to be prioritized over consumer 5G — as was the case for 5G launches in South Korea at the back end of last year.

“4G was a lot more driven by the consumer side and there was an understanding that you were going for national coverage that was never really a question and you were delivering on the data promise that 3G never really delivered… so there was a gap of technology that needed to be filled. With 5G it’s much less clear,” says Gartner’s Sylvain Fabre, discussing the tech’s hype and the reality with TechCrunch ahead of MWC.

“4G’s very good, you have multiple networks that are Gbps or more and that’s continuing to increase on the downlink with multiple carrier aggregation… and other densification schemes. So 5G doesn’t… have as gap as big to fill. It’s great but again it’s applicability of where it’s uniquely positioned is kind of like a very narrow niche at the moment.”

“It’s such a step change that the real power of 5G is actually in creating new business models using network slicing — allocation of particular aspects of the network to a particular use-case,” Forrester analyst Dan Bieler also tells us. “All of this requires some rethinking of what connectivity means for an enterprise customer or for the consumer.

“And telco sales people, the telco go-to-market approach is not based on selling use-cases, mostly — it’s selling technologies. So this is a significant shift for the average telco distribution channel to go through. And I would believe this will hold back a lot of the 5G ambitions for the medium term.”

To be clear, carriers are now actively kicking the tyres of 5G, after years of lead-in hype, and grappling with technical challenges around how best to upgrade their existing networks to add in and build out 5G.

Many are running pilots and testing what works and what doesn’t, such as where to place antennas to get the most reliable signal and so on. And a few have put a toe in the water with commercial launches (globally there are 23 networks with “some form of live 5G in their commercial networks” at this point, according to Fabre.)

But at the same time 5G network standards are yet to be fully finalized so the core technology is not 100% fully baked. And with it being early days “there’s still a long way to go before we have a real significant impact of 5G type of services”, as Bieler puts it.

There’s also spectrum availability to factor in and the cost of acquiring the necessary spectrum. As well as the time required to clear and prepare it for commercial use. (On spectrum, government policy is critical to making things happen quickly (or not). So that’s yet another factor moderating how quickly 5G networks can be built out.)

And despite some wishful thinking industry noises at MWC this week — calling for governments to ‘support digitization at scale’ by handing out spectrum for free (uhhhh, yeah right) — that’s really just whistling into the wind.

Rolling out 5G networks is undoubtedly going to be very expensive, at a time when carriers’ businesses are already faced with rising costs (from increasing data consumption) and subdued revenue growth forecasts.

“The world now works on data” and telcos are “at core of this change”, as one carrier CEO — Singtel’s Chua Sock Koong — put it in an MWC keynote in which she delved into the opportunities and challenges for operators “as we go from traditional connectivity to a new age of intelligent connectivity”.

Chua argued it will be difficult for carriers to compete “on the basis of connectivity alone” — suggesting operators will have to pivot their businesses to build out standalone business offerings selling all sorts of b2b services to support the digital transformations of other industries as part of the 5G promise — and that’s clearly going to suck up a lot of their time and mind for the foreseeable future.

In Europe alone estimates for the cost of rolling out 5G range between €300BN and €500BN (~$340BN-$570BN), according to Bieler. Figures that underline why 5G is going to grow slowly, and networks be built out thoughtfully; in the b2b space this means essentially on a case-by-case basis.

Simply put carriers must make the economics stack up. Which means no “huge enormous gambles with 5G”. And omnipresent ROI pressure pushing them to try to eke out a premium.

“A lot of the network equipment vendors have turned down the hype quite a bit,” Bieler continues. “If you compare this to the hype around 3G many years ago or 4G a couple of years ago 5G definitely comes across as a soft launch. Sort of an evolutionary type of technology. I have not come across a network equipment vendors these days who will say there will be a complete change in everything by 2020.”

On the consumer pricing front, carriers have also only just started to grapple with 5G business models. One early example is TC parent Verizon’s 5G home service — which positions the next-gen wireless tech as an alternative to fixed line broadband with discounts if you opt for a wireless smartphone data plan as well as 5G broadband.

From the consumer point of view, the carrier 5G business model conundrum boils down to: What is my carrier going to charge me for 5G? And early adopters of any technology tend to get stung on that front.

Although, in mobile, price premiums rarely stick around for long as carriers inexorably find they must ditch premiums to unlock scale — via consumer-friendly ‘all you can eat’ price plans.

Still, in the short term, carriers look likely to experiment with 5G pricing and bundles — basically seeing what they can make early adopters pay. But it’s still far from clear that people will pay a premium for better connectivity alone. And that again necessitates caution.

5G bundled with exclusive content might be one way carriers try to extract a premium from consumers. But without huge and/or compelling branded content inventory that risks being a too niche proposition too. And the more carriers split their 5G offers the more consumers might feel they don’t need to bother, and end up sticking with 4G for longer.

It’ll also clearly take time for a 5G ‘killer app’ to emerge in the consumer space. And such an app would likely need to still be able to fallback on 4G, again to ensure scale. So the 5G experience will really need to be compellingly different in order for the tech to sell itself.

On the handset side, 5G chipset hardware is also still in its first wave. At MWC this week Qualcomm announced a next-gen 5G modem, stepping up from last year’s Snapdragon 855 chipset — which it heavily touted as architected for 5G (though it doesn’t natively support 5G).

If you’re intending to buy and hold on to a 5G handset for a few years there’s thus a risk of early adopter burn at the chipset level — i.e. if you end up with a device with a suckier battery life vs later iterations of 5G hardware where more performance kinks have been ironed out.

Intel has warned its 5G modems won’t be in phones until next year — so, again, that suggests no 5G iPhones before 2020. And Apple is of course a great bellwether for mainstream consumer tech; the company only jumps in when it believes a technology is ready for prime time, rarely sooner. And if Cupertino feels 5G can wait, that’s going to be equally true for most consumers.

Zooming out, the specter of network security (and potential regulation) now looms very large indeed where 5G is concerned, thanks to East-West trade tensions injecting a strange new world of geopolitical uncertainty into an industry that’s never really had to grapple with this kind of business risk before.

Chinese kit maker Huawei’s rotating chairman, Guo Ping, used the opportunity of an MWC keynote to defend the company and its 5G solutions against U.S. claims its network tech could be repurposed by the Chinese state as a high tech conduit to spy on the West — literally telling delegates: “We don’t do bad things” and appealing to them to plainly to: “Please choose Huawei!”

Huawei rotating resident, Guo Ping, defends the security of its network kit on stage at MWC 2019

When established technology vendors are having to use a high profile industry conference to plead for trust it’s strange and uncertain times indeed.

In Europe it’s possible carriers’ 5G network kit choices could soon be regulated as a result of security concerns attached to Chinese suppliers. The European Commission suggested as much this week, saying in another MWC keynote that it’s preparing to step in try to prevent security concerns at the EU Member State level from fragmenting 5G rollouts across the bloc.

In an on stage Q&A Orange’s chairman and CEO, Stéphane Richard, couched the risk of destabilization of the 5G global supply chain as a “big concern”, adding: “It’s the first time we have such an important risk in our industry.”

Geopolitical security is thus another issue carriers are having to factor in as they make decisions about how quickly to make the leap to 5G. And holding off on upgrades, while regulators and other standards bodies try to figure out a trusted way forward, might seem the more sensible thing to do — potentially stalling 5G upgrades in the meanwhile.

Given all the uncertainties there’s certainly no reason for consumers to rush in.

Smartphone upgrade cycles have slowed globally for a reason. Mobile hardware is mature because it’s serving consumers very well. Handsets are both powerful and capable enough to last for years.

And while there’s no doubt 5G will change things radically in future, including for consumers — enabling many more devices to be connected and feeding back data, with the potential to deliver on the (much hyped but also still pretty nascent) ‘smart home’ concept — the early 5G sales pitch for consumers essentially boils down to more of the same.

“Over the next ten years 4G will phase out. The question is how fast that happens in the meantime and again I think that will happen slower than in early times because [with 5G] you don’t come into a vacuum, you don’t fill a big gap,” suggests Gartner’s Fabre. “4G’s great, it’s getting better, wi’fi’s getting better… The story of let’s build a big national network to do 5G at scale [for all] that’s just not happening.”

“I think we’ll start very, very simple,” he adds of the 5G consumer proposition. “Things like caching data or simply doing more broadband faster. So more of the same.

“It’ll be great though. But you’ll still be watching Netflix and maybe there’ll be a couple of apps that come up… Maybe some more interactive collaboration or what have you. But we know these things are being used today by enterprises and consumers and they’ll continue to be used.”

So — in sum — the 5G mantra for the sensible consumer is really ‘wait and see’.

Over the past year, we’ve written a lot about the rise of supergiant venture capital funds. Ever since the rollout of the $100 billion SoftBank Vision Fund, established VCs have been outdoing each other to raise ever-bigger funds.

But let’s not write the epitaph on smaller funds. U.S. venture fundraising data for 2019 reveals a lot of smaller, more focused funds closing on capital. Newcomers are rolling out fresh early-stage funds, and even established VCs are opting in many cases to keep fund size constant or even a bit smaller.

The influx of small and mid-sized funds serves as a reminder that supergiant funds are somewhat of an aberration for the venture capital industry. While VCs compete to back massively scalable startups, the common wisdom is the venture capital industry itself does not scale especially well. Adding more capital to the pot, the thinking goes, likely does more to inflate valuations than foster great companies.

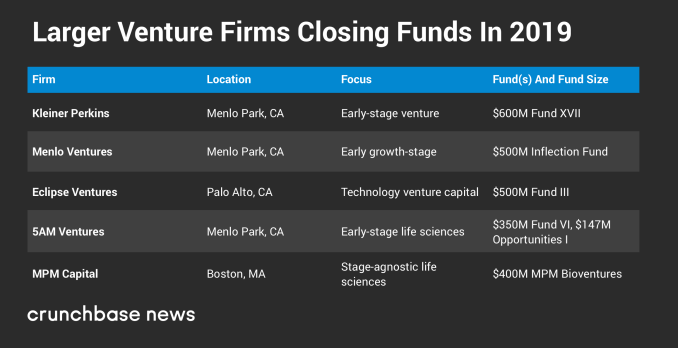

Silicon Valley stalwart Kleiner Perkins is among the latest to hop on the smaller-is-better bandwagon. Three weeks ago, the 47-year-old firm closed on $600 million for its eighteenth flagship fund, touting a plan to go “back to the future” and focus on early-stage with the philosophy that “venture is a non-scalable, boutique craft.”

Of course, $600 million is by no means a tiny fund. And Kleiner’s most prominent growth-stage investment partner, Mary Meeker, did just leave to start her own firm. Nonetheless, it is a step down from Kleiner’s last major fundraise in 2016, which brought in $1.4 billion for a growth-stage vehicle and an early-stage fund.

Meanwhile, Crunchbase fundraising data shows plenty of U.S. funds of $200 million or less closing in 2019, as well as several more that are apparently still in fundraising mode. So far, billion-dollar-plus funds are pretty scarce.

Below, we take a look at the venture fund Class of 2019, including newcomers, as well as follow-on funds from established firms. We also focus on rising stars, newer firms that have raised larger new funds.

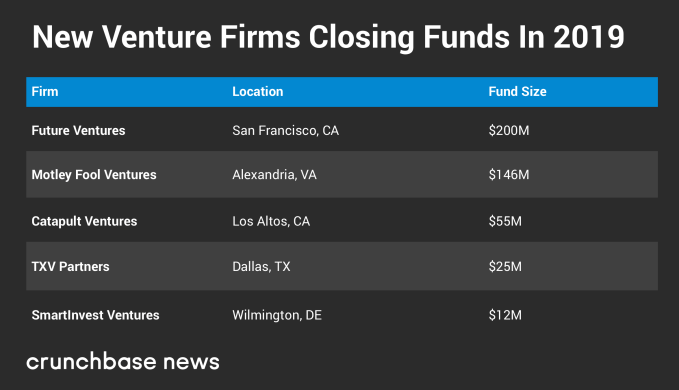

No matter how many existing venture firms are out chasing startups, there’s always a niche that some newcomer will identify as underserved. So far, 2019 has been no exception.

At least five U.S venture firms have announced closings on their inaugural funds this year.1

Probably the highest profile new entrant this year is from an already well-known Silicon Valley investor, Steve Jurvetson, founder and former managing partner of the 34-year-old VC firm DFJ. Jurvetson closed on $200 million this month for Future Ventures, which will focus on early-stage deals in areas including space exploration, quantum computing, AI and synthetic biology.

Another noteworthy newcomer is Motley Fool Ventures, which is an early-stage, tech-focused venture fund tied to The Motley Fool investment platform. In a twist on the typical VC model of raising capital from large institutional investors, contributors to the $146 million fund are primarily Motley Fool members.

Established VCs have been raising fresh cash, too. So far this year, we haven’t seen a pure-play venture capital firm close a U.S. fund of a billion dollars or more.2 However, we have seen a number of pretty big funds from well-known VCs.

Last week, Menlo Ventures, a longstanding Valley firm that led one of Uber’s early-stage rounds, closed on $500 million for its first Inflection Fund, which will focus on early growth-stage startups.

And on the biotech front, California-based 5AM Ventures proved the early-stage bird can get the follow-on investment, raising $500 million across two new funds. And on the East Coast, Boston-based MPM Capital closed on $400 million for its seventh flagship fund.

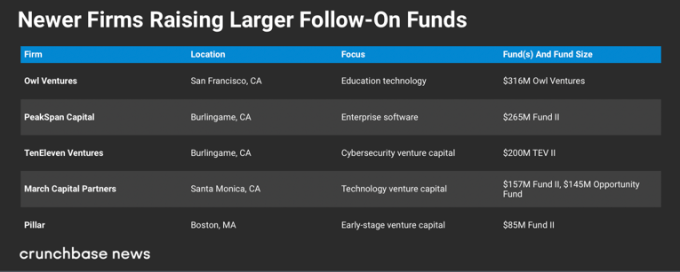

So far this year, we’ve also seen a number of relatively new venture capital firms raise upsized follow-on funds. By relatively new, we generally mean firms that closed their first fund less than five years ago.

Typically, when we see a firm raising a larger or stable-sized follow-on fund, it indicates a rising star. It usually means that their existing portfolio has seen some successes, and investors are optimistic about future prospects.

Edtech investor Owl Ventures meets this criteria. The five-year-old firm closed on $316 million for its third flagship fund this year. To date, San Francisco-based Owl has invested in at least 24 companies, with a couple of exits and a number of up-rounds under its belt.

Enthusiasm for the cybersecurity space boosted the fortunes of another firm on our rising star list, TenEleven Ventures. The five-year-old, Silicon Valley-based venture firm closed on $200 million for its second early-stage fund this month.

Clearly, not everyone can raise a billion-dollar venture capital fund. And not everyone wants to. For early-stage in particular, the longstanding practice of raising smaller and mid-sized funds is alive and well.

That said, a couple months of fundraising data does not necessarily indicate a long-term trend. We could see a string of billion-dollar-plus funds closing in the next few weeks. Or not.

For now, however, it looks like pressure to become the next SoftBank has ebbed some, with unicorn-chasing giants carving out their niche and smaller funds eyeing other opportunities.

We focused on U.S.-based firms raising funds that make investments in U.S. companies. This does not include, for instance, a Silicon Valley-headquartered firm raising a China-focused fund.

We also did not include Spark Capital, which has submitted securities filings laying out plans to raise a $400 million sixth flagship fund and an $800 million growth-stage fund. The New York and Boston-based firm, known for its early investments in Twitter, Slack, Coinbase and other unicorns, is widely expected to meet or exceed its fundraising goals, but it has not yet officially closed the funds.

Editor’s Note: Technology, startups, entrepreneurship, unicorns, S-1s. Silicon Valley has created an economic engine unlike any other in the world over the past few decades. That success has come with incredible influence over our society, politics, and economy, an influence that is increasingly under the microscope. Our industry has gained outsized power, and now it needs to meet that power with outsized responsibility.

In a new series for TechCrunch Extra Crunch, Greg Epstein, the humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT, will interrogate issues of ethics and how they apply to technology and startups today. As Epstein writes:

In 2018 I joined MIT in addition to my role at Harvard, and the experience of becoming a chaplain at what is officially a technology institute inspired me to reorient much of my work toward helping people think about and create ethical lives in a technological world.

I’ve essentially moved from studying religion to studying tech, and it’s a surprisingly natural transition. After all, the late great tech critic and ethicist Neil Postman first wrote about the idea of a religion of technology back in 1992, expressing concern about the role of the fax machine in modern society.

And regardless of what you believe, the ‘religion of tech,’ if such a thing exists, would likely have more followers than any other religion in the world. The question I’m most interested in asking, then, is: how do our values shape the technology we create? Well, that and its inverse: how is our technology shaping our values?

Today, Epstein interviews Anand Giridharadas, who has become one of the world’s most prominent critics of inequality and inequity in contemporary capitalism. His book Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World has triggered a conversation around the implications of our economic structure and what should be done about it.

In Cambridge today, Epstein and his office will be awarding the Rushdie Award to Giridharadas for his humanist achievements, and Giridharadas will keynote the “Social Enterprise Conference” at Harvard.

This interview is approximately 5,300 words / 22 minutes read time. The first third has been ungated given the importance of this subject. To read the whole interview, be sure to join the Extra Crunch membership. ~ Danny Crichton

Photo by Michael S. Schwartz/Getty Images

Greg Epstein: How would you summarize your argument in Winners Take All?

Anand Giridharadas: The heart of the argument is that we live in an age of staggering inequality, that is fundamentally about a monopolizing of the future itself. The winners of our age, the people who manage to be on the right side of an era of precipitous change and churn, have managed to build, operate, and maintain systems that siphon off most of the fruits of progress to them.

I don’t think there’s a person alive today who would deny that this has been a very fertile age for innovation. That there’s been no shortage of new stuff invented, new promise, new companies, new capital expenditure.

Take any measure of … I often joke, innovation is the Latin word for new shit. I don’t think anybody would say, “I feel shortchanged in the absolute level of new shit in this age.” I’m not sure what age you would preferred to have lived in.

But if you go to many, many societies, including the one you and I live in, but many others, and you ask people, “What about progress?”, which is most people’s lives getting better, in my definition, I think it would also be hard to deny that many, if not most people, in certainly the advanced countries, will tell you, “No. I haven’t experienced much progress, and I do feel shortchanged on that score.”

And so, if you start with the premise of how is it that we live in an age of tremendous innovation, and for so many people, so little progress, the answer is the winners of our age have cornered the fruits of innovation, so that they fail to translate into progress.

And, at the heart of what I’m trying to establish with the book, is how they have then turned around, and in response to this exclusion, and the anger it generates, sought to pass themselves off as change agents who can fix the problem that they are complicit in causing, and who can fight the fire that they helped set.

This is not the first generation of ultra rich people in history to seek to justify their own rule, but they’ve found a particularly ingenious way to do it, which is to seek to be the solution to the problem that they are still actively working to cause.

Greg: What do you say to the folks who would say it’s not just new shit, as you put it so well, but that all the new shit, even if there is more inequality, adds up to a better quality of life for everybody? That yeah, there is rising inequality, but everybody’s driving around in a car, everybody’s on the phone. People are by and large living longer. They’re living more healthily. They’re living with less violence.

Greg Epstein. Photo via Humanist Hub

Anand: No. That’s false. Life expectancy has gone down, for the last three years, in America. Do people know that? Do the readers of TechCrunch know that life expectancy has gone down in America? Do the readers of TechCrunch know how rare that is in history, for life expectancy to go down?

Think about the last time you went to the doctor. Think about all the tests they do these days. We have two children. We have a one-year-old and a four-year-old. Between the birth, between the pregnancy with the four-year-old, and the pregnancy with the one-year-old, there were several new tests, and new technologies invented, that we had access to with the one-year-old, that weren’t ready yet when we had the four-year-old. That’s how much new shit there is. So, how is life expectancy going down?

I start the book with all these stats, and try to separate out the innovation from the progress. Literacy has not improved in America, even though all these books have been scanned. Another area that the TechCrunch reader would surely point to, as well, it’s become easier than ever to start your own business and be an entrepreneur. One third as many young people today own their own business, as they did in the 80s. One third as many. The average twelfth grader tests more poorly in reading today, than in 1992.

If you think about all the new tests, going back to that medical example, all the new diagnostics, all the new genetic work that has been done, it really actually requires a tremendous amount of rigging to have all of that go into one end of the machine, and have a decline in life expectancy come out of the other.

That’s not a natural occurrence. The natural occurrence would be for people to live longer, because of all the stuff that’s happened. You have to really jury rig the society, to ensure that somehow a very large number of people are unaffected by that positive stuff, and in fact are subjected to a bunch of negative stuff that the positive stuff can’t touch.

Greg: I think what we’re told is that the positive stuff would not be possible, if it wasn’t for that jury rigging. And I think what you’re doing, and a number of people are doing, is pushing back against that narrative.

Anand: That’s at the heart of this whole thing. That is the religion that my book seeks to slay, is the religion of win-win-ism, which is a false religion. And it is a religion that says that it’s true in both its win-win form, and its inverse lose-lose form.

What win-win-ism says is, the best way to help the least among us is to do what’s good for the richest and most powerful. The best guide to what’s going to be good for America is going to be what’s good for Jeff Bezos, and Amazon, and Facebook, and Google, and Goldman Sachs. But, the inverse is also true. The win-win religion holds that if you do anything that has any cost, significant cost, for the winners of our age, you will only be hurting the most powerless among us.

Greg: I’m fascinated by the way you speak of win-win-ism as a religion — in the book you also talk about how high-powered consultants at places like McKinsey subscribe to a ‘religion of facts.’ And in a profile piece on Justin Rosenstein of Asana, you portray him sitting around a table in Silicon Valley, talking about community and saying a secular grace. It seemed like you were trying to show that what you call this “religion” even has its own rituals, its own congregations.

And it’s not just you: I’ve been studying the intersection of secularism and religion for almost 20 years, and now that I’ve started to work on the ethics of technology, I’ve noticed almost everyone I’m reading seems to refer to technology as a kind of secular religion. I’m wondering what’s going on there.

What’s the importance of using those terms, for you? How does that help your argument?

Anand: I think it’s actually helpful to understand as a religion to understand how removed it is from reality. Because, otherwise, you’re left with the puzzle of how can people at Silicon Valley continue to spread the narrative that as long as you sprinkle their algorithms on things, they will tend toward equality, justice, and emancipation.

They’re still spreading that narrative now. I mean, it’s blockchain today, and tomorrow it will be something else. But, we now have 25, 30 years of evidence that in fact these technologies played into existing power divides, and in many cases accentuated them.

I mean, with all the whole supposedly leveling tech revolution, fewer companies now run America than did before the tech revolution. And they all know this at some level. They understand the facts. They understand that we do live in this winners-take-all world that has been rich-splained to us as being some kind of new age of emancipation.

To my mind, the only way they can keep believing is as an act of faith. I don’t think it’s possible to look at the world right now, and objectively say what they continue to say, which is that them being in charge, these technologies being in charge, rich people doing more of what they have been doing, it’s gonna save us. You can only maintain this view if it’s a faith, constantly re-evangelized. And that’s why I think they spend so much time in conferences. I think if they were at home more, or in the office more, I think they would really fall prey to doubts.

Greg: The conference is sort of the revival meeting of the tech religion.

Anand: It is 100% a revival meeting, yes. And I think they need it.

Photo by Patrick Nouhailler via Flickr used under Creative Commons

Greg: Venture capitalists are another parallel I see to religion. You mention how they are seen today as thinkers, philosophers. I tend to think of VC’s as priests in the tech religion. What reaction have you been getting from that community in particular? From tech VC’s, or from Silicon Valley as a whole?

Anand: I hear anecdotally, first of all, that Winners Take All has caused a lot of discussion in the Valley. People text me from dinner parties saying, “Oh my god, a fight just broke out at my dinner party about your book.” And I would say the Valley has probably been the most resistant to my critique. But a lot of people, even in the stratospheres I write about, understand that there is something badly wrong, the system needs to seriously change.

A lot of people reach out to me [privately] and say, “look, I don’t know quite how to get there, but I kind of agree with you that I’m living on top of an indefensible mountain here. And I’m not sure how to get down. I’m not necessarily even sure how I got up here, but I’m aware that this is an indefensible mountain, and I’m aware that I should not be on it. Let’s talk.” But, in Silicon Valley in general, I think there has been the most resistance. Because [many] are truly possessed of the feeling that leaving them alone, and letting them do whatever they want to do, and grow however they want to grow, is what is best for the world.

My best read on someone like Mark Zuckerberg is that he sincerely feels that he was a rare, lucky person in history who has the privilege of having certain knowledge, and insight, and an idea that if he is left alone to pursue to its fullest will emancipate the world more than maybe any government, more than maybe any social movement, etc. I think Zuckerberg genuinely feels, and I have sort of come to understand this from people who know him, and understand how he thinks, that journalists asking him questions, or regulators pushing back, are essentially deferring his emancipation of the world. I don’t think that makes him … I don’t think he is a cynic. And that’s why he is so difficult to deal with. I think he is a true believer. But that makes him in some ways even more difficult for us to deal with.

Greg: I mean, in the religion metaphor that would make him more like a Messianic figure.

Anand: Which he absolutely is.

Greg: Right. In religious history, some Messianic figures actually believe their Messianism.

Anand: Right. And I think in some ways our society is better protected against a Goldman Sachs fighting for bad policy in Washington, making a bunch of money on it, and then throwing five million dollars at a women’s shelter. We’re not great at it, but if you think of the financial industry, we regulate the hell out of them. It’s not perfect, but we are all up in their grill.

There are people at the SEC watching every trail. And I think that’s because everybody understands the game, like, they’re trying to make money. I love people in finance, because no one in finance has ever tried to convince me that they’re not in finance, or they’re not motivated by finance.

I have never ever in my life had a meeting, or an interview with someone in finance who is like, “Well, our business is really about inspiring connection through money in our communities.”

Greg: I have actually had that exact meeting, by the way.

Anand: That’s kind of amazing. But, in general, people in finance own the idea that they work in finance. Whereas, with tech, I think a lot of our culture has bought into the idea that there are these figures of emancipation, and liberation, and social leveling. And it has bought them a tremendous [amount] of space and freedom that they have exploited and abused.

Granted, this news is maybe a bit too late. Samsung’s already sold out of the free Galaxy Buds it was throwing in with S10 pre-orders. That said, the new Bluetooth earbuds are worth the $129 asking price, especially for Galaxy device owners.

As with many fellow S10 reviewers, I’ve been using the Buds for about a week now. They happily hitched a ride in my ears from San Francisco to Barcelona and then back home to New York. And I’ve been digging them the whole time.

This certainly isn’t Samsung’s first wireless earbud rodeo, but frankly, it took the company taking more than a few pages out of Apple’s playbook to get things right here.

The Galaxy Buds are heavily inspired by the AirPods’ simple “just works” approach to the category, bucking Samsung’s tendency to overstuff products. That approach mostly works like a charm on handsets, but the best thing a set of earbuds can do is fade into the background. On that front, the Galaxy Buds work like a charm.

The AirPod comparisons are clear the moment you open the Galaxy Buds case the first time, triggering a dialog box on the screen of your Galaxy device. Like Apple’s version, the headphones will work with any Bluetooth device, but they work best with the company’s own products. Ecosystems, people. For other Android devices, you’ll need to download Samsung’s SmartThings or Galaxy Wearable apps for the proper effect.

The charging case itself is a bit more bulky and bulbous than the AirPods, but it’s certainly small enough to carry around in your jeans pockets. I also actually kind of prefer the pill shape to Apple’s Glide dental floss design.

The case offers two other distinct advantages:

Apple’s no doubt working on that latter bit with the AirPods 2 (remember AirPower?), but Samsung’s beat the company to the punch here — and for that matter, with Wireless PowerShare, which lets you charge the case by simply placing it on the back of the S10. That was one less cable I needed to pack.

The battery should last you a while regardless. The Buds are 58 mAh each and the case is 252 mAh. That should translate to six hours a go on the Buds and seven hours with the case. I know I didn’t run out of juice during the day.

The Buds fit well and the silicon tips should ensure they fit more ear sizes. They also form a nice seal, keeping sound in and passively canceling out ambient noise. They’ll stay put pretty well — I didn’t have any issues keeping them on at the gym. The sound, tuned by Samsung-owned AKG, is solid. It’s not the best I’ve heard in a pair of wireless buds, but it’s perfectly fine for walking around and hitting the coffee shop.

All in all, a nice little surprise from Samsung, and a great addition to the Galaxy ecosystem. Perhaps they’re even good enough to convince Samsung to drop the headphone jack — but hopefully not.