The Standardized Unit of Smell Is Known As What? |

|

Think you know the answer? |

|

from How-To Geek https://ift.tt/2L3Zcr9

The Standardized Unit of Smell Is Known As What? |

|

Think you know the answer? |

|

Owen Williams / Motherboard:

By putting Edge on Chromium and planning to invest in the engine, Microsoft is showing it is committed to the web as a platform for the future of apps — The move will allow deeper integration of Chromium and Chrome on Windows, which will lead to major improvements in performance and battery life.

Mike Masnick / Techdirt:

Facebook bans sexual solicitation including vague suggestive statements, sexualized slang, and using sexual hints such as mentioning sexual preference — Well, well. As we've covered for a while now, FOSTA became law almost entirely because Facebook did an about-face on its position on the law …

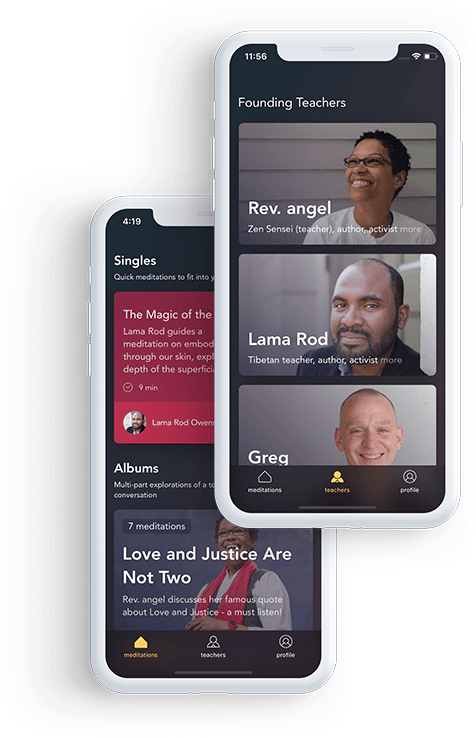

A mindful, contemplative approach to internalized racism and sexism is a necessary piece of the puzzle of dismantling systems of oppression, Awaken founder and CEO Ravi Mishra says. That’s the entire point of Awaken, a mindfulness and meditation app specifically geared toward helping people cope with the harsh realities of today’s society.

Awaken got its roots in the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. presidential election, Mishra told TechCrunch. The election surfaced these “larger questions that have to do with race, gender, sexuality and power, and how they live inside of us.”

Through Awaken, Mishra hopes to offer mindfulness and meditation practices that help cultivate stability within marginalized communities. These contemplative practices center around sitting with certain questions and identity construction. Awaken’s founding teachers are Rev. Angel Kyodo Williams, Lama Rod Owens and Sensei Greg Snyder — three leaders focused on the intersection of mindfulness and social change.

Similar to meditation app Headspace, which is valued at $320 million, Awaken has a freemium plan in place. For full access to content, Awaken charges $8.99 a month. While Awaken does seek to make money, Mishra says he’s not doing it for profit. Instead, the plan is to use all the money Awaken makes for activist work.

“We’re currently running at a loss and figuring out how to break even,” he told me. “The hope and idea is once we are fully profitable, we’ll move that into activist work.”

Awaken has plans to close a round of funding from mission-aligned angel investors early next year.

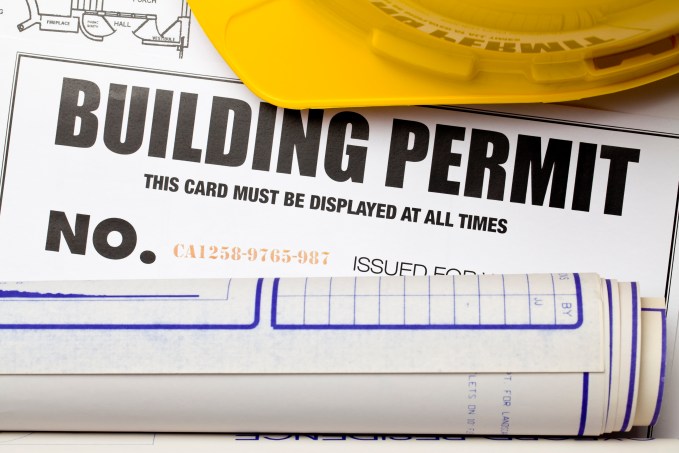

When the hell did building a house become so complicated?

Don’t let the folks on HGTV fool you. The process of building a home nowadays is incredibly painful. Just applying for the necessary permits can be a soul-crushing undertaking that’ll have you running around the city, filling out useless forms, and waiting in motionless lines under fluorescent lights at City Hall wondering whether you should have just moved back in with your parents.

Consider this an ongoing discussion about Urban Tech, its intersection with regulation, issues of public service, and other complexities that people have full PHDs on. I’m just a bitter, born-and-bred New Yorker trying to figure out why I’ve been stuck in between subway stops for the last 15 minutes, so please reach out with your take on any of these thoughts: @Arman.Tabatabai@techcrunch.com.

And to actually get approval for those permits, your future home will have to satisfy a set of conditions that is a factorial of complex and conflicting federal, state and city building codes, separate sets of fire and energy requirements, and quasi-legal construction standards set by various independent agencies.

It wasn’t always this hard – remember when you’d hear people say “my grandparents built this house with their bare hands?” These proliferating rules have been among the main causes of the rapidly rising cost of housing in America and other developed nations. The good news is that a new generation of startups is identifying and simplifying these thickets of rules, and the future of housing may be determined as much by machine learning as woodworking.

Photo by Bill Oxford via Getty Images

Cities once solely created the building codes that dictate the requirements for almost every aspect of a building’s design, and they structured those guidelines based on local terrain, climates and risks. Over time, townships, states, federally-recognized organizations and independent groups that sprouted from the insurance industry further created their own “model” building codes.

The complexity starts here. The federal codes and independent agency standards are optional for states, who have their own codes which are optional for cities, who have their own codes that are often inconsistent with the state’s and are optional for individual townships. Thus, local building codes are these ever-changing and constantly-swelling mutant books made up of whichever aspects of these different codes local governments choose to mix together. For instance, New York City’s building code is made up of five sections, 76 chapters and 35 appendices, alongside a separate set of 67 updates (The 2014 edition is available as a book for $155, and it makes a great gift for someone you never want to talk to again).

In short: what a shit show.

Because of the hyper-localized and overlapping nature of building codes, a home in one location can be subject to a completely different set of requirements than one elsewhere. So it’s really freaking difficult to even understand what you’re allowed to build, the conditions you need to satisfy, and how to best meet those conditions.

There are certain levels of complexity in housing codes that are hard to avoid. The structural integrity of a home is dependent on everything from walls to erosion and wind-flow. There are countless types of material and technology used in buildings, all of which are constantly evolving.

Thus, each thousand-page codebook from the various federal, state, city, township and independent agencies – all dictating interconnecting, location and structure-dependent needs – lead to an incredibly expansive decision tree that requires an endless set of simulations to fully understand all the options you have to reach compliance, and their respective cost-effectiveness and efficiency.

So homebuilders are often forced to turn to costly consultants or settle on designs that satisfy code but aren’t cost-efficient. And if construction issues cause you to fall short of the outcomes you expected, you could face hefty fines, delays or gigantic cost overruns from redesigns and rebuilds. All these costs flow through the lifecycle of a building, ultimately impacting affordability and access for homeowners and renters.

Photo by Caiaimage/Rafal Rodzoch via Getty Images

Strap on your hard hat – there may be hope for your dream home after all.

The friction, inefficiencies, and pure agony caused by our increasingly convoluted building codes have given rise to a growing set of companies that are helping people make sense of the home-building process by incorporating regulations directly into their software.

Using machine learning, their platforms run advanced scenario-analysis around interweaving building codes and inter-dependent structural variables, allowing users to create compliant designs and regulatory-informed decisions without having to ever encounter the regulations themselves.

For example, the prefab housing startup Cover is helping people figure out what kind of backyard homes they can design and build on their properties based on local zoning and permitting regulations.

Some startups are trying to provide similar services to developers of larger scale buildings as well. Just this past week, I covered the seed round for a startup called Cove.Tool, which analyzes local building energy codes – based on location and project-level characteristics specified by the developer – and spits out the most cost-effective and energy-efficient resource mix that can be built to hit local energy requirements.

And startups aren’t just simplifying the regulatory pains of the housing process through building codes. Envelope is helping developers make sense of our equally tortuous zoning codes, while Cover and companies like Camino are helping steer home and business-owners through arduous and analog permitting processes.

Look, I’m not saying codes are bad. In fact, I think building codes are good and necessary – no one wants to live in a home that might cave in on itself the next time it snows. But I still can’t help but ask myself why the hell does it take AI to figure out how to build a house? Why do we have building codes that take a supercomputer to figure out?

Ultimately, it would probably help to have more standardized building codes that we actually clean-up from time-to-time. More regional standardization would greatly reduce the number of conditional branches that exist. And if there was one set of accepted overarching codes that could still set precise requirements for all components of a building, there would still only be one path of regulations to follow, greatly reducing the knowledge and analysis necessary to efficiently build a home.

But housing’s inherent ties to geography make standardization unlikely. Each region has different land conditions, climates, priorities and political motivations that cause governments to want their own set of rules.

Instead, governments seem to be fine with sidestepping the issues caused by hyper-regional building codes and leaving it up to startups to help people wade through the ridiculousness that paves the home-building process, in the same way Concur aids employee with infuriating corporate expensing policies.

For now, we can count on startups that are unlocking value and making housing more accessible, simpler and cheaper just by making the rules easier to understand. And maybe one day my grandkids can tell their friends how their grandpa built his house with his own supercomputer.

Mix / The Next Web:

Researchers: 415,000+ routers from around the world, including a majority from MikroTik, have been infected with malware to mine CoinHive, Omine, and CoinImp — Researchers have discovered over 415,000 routers across the globe have been infected with malware designed to steal their computing power and secretly mine cryptocurrency.

BuzzFeed News:

Sources: FBI is now investigating fake net neutrality comments on the FCC website and has delivered subpoenas to at least two organizations — People's names and addresses were listed on the FCC's website beside net neutrality comments they didn't make. Now the FBI is interested.

Once upon a time, there were two companies. Microsoft was the big, bad giant who ruled over everyone. While Apple was the small, unassuming entity who nobody loved. Many years passed, and without anyone realizing it, the two companies switched places.

Now, Apple is in command, with its legion of slavish followers. And Microsoft is the underdog, fighting to survive in a world that’s changing before its very eyes. But one thing hasn’t changed, and that’s the way Microsoft attacks Apple in order to sell its products.

That introduction was a roundabout way of introducing the first Microsoft ad for the holidays. It’s an ad for the Surface Go, but in order to help sell the Surface Go, Microsoft took a swipe at Apple and its iPad. Which apparently isn’t a real computer.

Microsoft’s new Surface Go ad is based on alternative version of “Grandma Got Run Over By a Reindeer” by Elmo and Patsy. It’s a terrible song in the first place, and Microsoft has managed to make it even worse in order to persuade you to buy a Surface Go.

The ad opens with a little girl singing, “Grandma, don’t run out and buy an iPad. Fine when I was six, but now I’m 10. My dreams are big, so I need a real computer. To do all the amazing things I know I can.” The assertion being the iPad isn’t a real computer.

If the iPad isn’t a real computer, then what is? Why, a Surface Go, of course. Because it can help you learn to code, and help you “help the gentle manatee”. Which may just be the strangest pairing since John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

Perhaps Microsoft is right here, and the iPad isn’t a real computer. But that isn’t the point. The point is by mentioning Apple’s products at every opportunity Microsoft is showing itself up as the underdog, and giving Apple extra publicity it doesn’t need.

Microsoft launched the $399 Surface Go in July 2018. And it’s the latest Windows-powered tablet designed to compete with the Apple iPad. Meanwhile, Apple launched its latest iPad Pro alongside the new MacBook Air and Mac Mini in October 2018.

Read the full article: Microsoft Claims the iPad “Isn’t a Real Computer”

Nikhilesh De / CoinDesk:

Coinbase adds Civic, district0x, Loom Network, and Decentraland to its Coinbase Pro trading platform and is considering 27 other tokens — UPDATE, 12/7/18 18:00 UTC: Four hours after announcing the list, Coinbase Pro said it was launching support for Civic, District0x, Loom Network and Decentraland's tokens.

When Apple announced its latest Series 4 Watch with electrocardiogram features, my mom took a sigh of relief, and then proceeded to set a reminder to order one for my dad. That’s because we found out last year, by chance, that he has atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is an irregular heartbeat, often times rapid heart rate that can increase your risk of stroke, heart failure and other heart-related issues.

The ECG feature, which monitors your heart rhythm and can detect AFib,* went live just two days ago. Already, at least one person has benefited from it.

Yesterday, a person on Reddit shared how their Apple Watch notified them of an abnormal heart rate. From there, they ran the ECG app and found out it was AFib. They went to urgent care and saw a doctor who they say said, “You should buy Apple stock. This probably saved you. I read about this last night and thought we would see an upswing this week. I didn’t expect it first thing this morning.”

The patient says they proceeded to go to a cardiologist the next day, who did an exam and confirmed the AFib diagnosis.

“I’m scheduled to go back in a week for some additional tests to start looking at the cause… blood, thyroid, etc…,” they wrote. “He also scheduled me with a partner who specializes more in the electrical side of things to have it looked from that angle as well.”

As one of the first more widely-owned ECG monitors, this could make a huge difference in the number of people who have at least some transparency into their heart health. But to be clear, once you enable the new feature, the watch is still not constantly looking for AFib. When the heart rhythm monitor detects something is off — a skipped or rapid heartbeat, for example — it will send a notification to your wrist.

That’s when you open up the ECG app, rest your arm on your lap or table, and then hold your finger to the crown for 30 seconds. From there, the watch will tell you if there are signs of atrial fibrillation.

If you want to learn more about the features, check out my colleague Brian Heater’s piece below.

Marcus Stroud and Brandon Allen met six years ago as roommates at Princeton University. The pair bonded over a common interest and a shared dream: to be venture capitalists.

“We were at a lecture and there were a couple VCs on campus speaking,” 25-year-old Stroud told TechCrunch. “Being a kid from a small town in Texas, Princeton was already a huge culture shock, but hearing about a world of VC, investment banking and private equity just really intrigued me.”

In 2016, Stroud and Allen graduated. Stroud, a former linebacker on the Princeton football team, went off to Wall Street where he was a fixed income analyst, and then to Austin, where he joined the alternative asset manager Vida Capital to learn the ins and outs of investing. Twenty-four-old Allen, meanwhile, clocked in about two years as a consultant.

It didn’t take long for the aspiring VCs to find their way back to each other to finally start on the project they had discussed in their dorm room. Over the last several months, Allen and Stroud have been quietly building a Dallas-based venture firm called TXV Partners. Their lofty target: $50 million, which would be the largest fund ever for an all-black line-up of general partners, an especially notable feat given Allen and Stroud are located in a market largely ignored by the storied VC firms of Silicon Valley.

TXV co-founder and general partner Marcus Stroud

Stroud and Allen plan to spend the $50 million on millennials. That is, millennial-friendly startups in the consumer, fintech and blockchain verticals, of which they’ll provide between $500,000 and $3 million in equity funding. So far, they’ve invested in one company, an Austin-based blockchain music platform called Matter Music.

Thanks to Stroud’s time on Princeton’s football team and his father, who is a former NFL player, TXV has tapped some athletic talent to support the fund and its portfolio companies. Former NFL player and Northgate Capital managing director Brent Jones is a mentor, and the firm’s advisors include athletes-turned-investors Torii Hunter and Steve Wisniewski, a former professional baseball player and NFL player, respectively.

A rapid transit train (DART) with the skyline of Dallas, Texas in the background

Allen is leading the firm’s Dallas office and Stroud is scouting full-time for startups in Austin, which is already a well-known source of tech talent.

“We wanted to be part of the next great VC hub,” Allen told TechCrunch. “We felt like it made sense and we felt comfortable in Texas. The thought of moving to San Francisco was out of reach for us. Texas has the opportunity to be at the forefront of what the next generation of technology will look like.”

With large universities feeding the talent pool, Texas has the potential but has yet to fully emerge as a force to be reckoned with for technology investors, even with the buzz surrounding Austin’s rising startup ecosystem. So far this year, companies headquartered in Texas have raised roughly $2.5 billion, on par with levels seen in the state in recent years, according to PitchBook. California startups, for context, have raised more than $50 billion this year.

Texas has the opportunity to be at the forefront of what the next generation of technology will look like. TXV co-founder Brandon Allen

In Austin this year, startups have pulled in $1.4 billion, just north of the $1.3 billion in total capital commitments in 2017. Dallas startups, for their part, have raised just $600 million across 87 deals. Deal count in Dallas actually looks to be dropping, hitting 173 in 2013, 143 in 2016 and falling down to 106 last year, but localized funds like TXV’s may help push the city’s tech scene forward.

Stroud and Allen are not only first-time general partners of what may become a multi-million-dollar VC fund, but they’re also two African Americans in a field dominated by white men. For them, it’s high stakes and failure is not an option.

VC is known for its lack of diversity. Indeed, 81 percent of VC firms don’t have a single black investor, according to data collected by Richard Kerby, a partner at Equal Ventures. Roughly 50 percent of black investors in the industry are at the associate level, or the lowest level at a firm, and only 2 percent of VC partners are black.

Base10 Partners’ $137 million fund, announced in September, is the largest black-led VC fund to date, but only one of the two general partners are black. Based in San Francisco, Base10 is run by two veteran investors with a well-established network in the Bay Area. The challenges for TXV are much larger, and the barriers may be much tougher to overcome.

“We’re young, black and in Texas,” Allen added. “We’re trying to do it differently. We wanted to really see if we can redefine the VC model from the bottom up. It’s important for Texans, for African Americans and for millennials.”

Brandon Allen and Marcus Stroud want to bring more diversity to venture capital

Allen was raised in New England and Stroud in Prosper, Texas, a small town outside of Dallas. Neither of them comes from wealth, as many Stanford-educated Silicon Valley elite do. They’ll have to put a lot of blood, sweat and tears into TXV, but if they succeed — and even if they don’t — they’ll have helped paint a new archetype for VCs.

“African Americans aren’t that well represented on either side of the table as an investor or a startup founder,” Stroud said. “I think, if anything, that doesn’t discourage us, it just makes us feel proud and empowered that we have an opportunity to help cultivate a fund that is majority minority-led. It’s something that fires me up.”

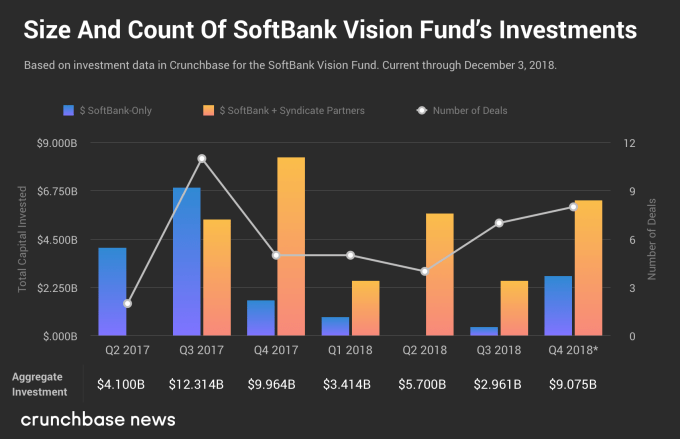

Much has been said about the SoftBank Vision Fund (SBVF), mostly in awe of the size of the investment vehicle.

It’s important to remember that the $100 billion number most often associated with the gargantuan fund is only a target. Today, however, the Vision Fund inched yet closer to that 12-figure goal as it continues to pour billions of dollars into technology companies around the world.

So far in 2018 the SoftBank Vision Fund has invested in more than 20 deals, accounting for over $21 billion in total investment. That sum didn’t all come from the Vision Fund of course — SoftBank’s Vision Fund typically invests alongside one or more syndicate partners who help fill out bigger rounds — but the amounts are nonetheless staggering. The chart below shows the Vision Fund’s investments since its inception in 2017.

In an annual Form D disclosure filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission this morning, SBVF disclosed that it has raised a total of approximately $98.58 billion from 14 investors since the date of first sale on May 20, 2017. The annual filing from last year said there was roughly $93.15 billion raised from 8 investors, meaning that the Vision Fund has raised $5.43 billion in the past year and added six new investors to its limited partner base.

In a financial report from November, SoftBank Group Corp disclosed (p. 21, Note 1) it has invested an additional $5 billion in the fund, which is “intended for the installment of an incentive scheme for operations of SoftBank Vision Fund.” It brings SoftBank’s total contribution to $21.8 billion, in line with original targets.

The most recent Form D also cites six more limited partners. Crunchbase News presumes that the $430 million in new capital we cannot source back to SoftBank came from those new partners. SoftBank declined to comment on who they are.

One of the primary challenges an investor as big as the Vision Fund faces is sourcing capital. SoftBank doesn’t have a lot of choice about who it can take on as limited partners. To fill out a $100 billion fund (or something larger), government-backed investors are some of the only market participants with the financial wherewithal to anchor its limited partner base. And, sometimes, international politics and venture finance collide.

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund committed $45 billion to the SBVF; it’s the single biggest backer of the fund. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is implicated in the extrajudicial torture, murder, dismemberment and disposal of Saudi dissident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi in early October.

In November, TechCrunch reported that SoftBank would wait for the outcome of Khashoggi’s murder investigation before it decides on Vision Fund 2. New revelations this weekend close the window of reasonable doubt around bin Salman’s involvement in the murder.

This past weekend, The Wall Street Journal reported that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency intercepted 11 messages sent between bin Salman and one of his closest aides, who allegedly oversaw the execution squad, in the hours before Khashoggi’s death. Amid mounting international and intelligence community consensus, though, the White House continues to defend Saudi Arabia.

Given these recent developments, it’s uncertain how SoftBank’s relationship with the Vision Fund’s principal backer will change going forward. Whether anything changes at all is itself an unknown at this point too.

SoftBank COO Marcelo Claure said there was “no certainty” of a follow-up fund back in mid-October.