The two people who sat down in reception without an appointment would not leave the startup’s office until the end of the day.

Two months later, a letter followed informing the company it had been suspended from the United Kingdom’s register of licensed sponsors, the database of companies the government has approved to employee foreign workers. The business had 20 working days from the typed date to make “representations” and submit “evidence” and “supporting documents” to counter the “believed” infractions spread across 12 pages, threaded through with copious references to paragraphs, annexes and bullet points culled from the Home Office‘s official guidance for sponsors.

Early in the new year another letter arrived, and an assessment process that had begun with an unannounced visit one autumn morning delivered its final verdict: The revocation of Metail‘s sponsor license with immediate effect.

“There is no right of appeal against this decision,” warns paragraph 64 of the 22-page decision letter — in text which the sponsor compliance unit has seen fit to highlight in bold. “Whilst your client can no longer recruit sponsored workers under Tier 2 and 5 of the Points Based system, they can continue to recruit UK and EEA workers as well as non-EEA nationals that have the right to work in the UK. The revocation of the license does not stop a business from trading,” the letter concludes. Tier 2 is the general work visa for regular employees, while Tier 5 is for temporary workers.

The government department that oversees the UK’s immigration system gets to have — and frame — the last word.

London-based Metail is a decade-plus veteran of the virtual fitting room space, its founders having spied early potential to commercialize computer vision technology to enable individualized sales assistance for online clothes and fashion shopping. It now sells services to retailers including photorealistic 3D body models to power virtual try-ons; algorithmic size recommendations; and garment visualization to speed up and simplify the process of showcasing fashion products online.

In the story below, we’ll look at how Metail’s situation sits within wider issues facing startups in the United Kingdom today. We also dig into the details of the company’s encounters with immigration rules, and what startups in the UK can do to hire the people they need without similar problems, in this article for Extra Crunch subscribers.

Metail has approached research-heavy innovation in the field of 3D visualization with determined conviction in transformative commercial potential, tucking $32 million in VC funding under its belt over the years, and growing its team to 40 people (including 11 PhDs) at a head office in London and a research hub located close to Cambridge University where its British founder studied economics in the late ’90s. It’s also racked up an IP portfolio that spans computer vision, photography, mechanics, image processing and machine learning — with 20 patents granted in the UK, Europe and the US, and a similar number pending. Years of 3D modeling expertise and a substantial war-chest of patents might, reasonably, make Metail an acquisition target for an ecommerce giant like Amazon that’s looking to shave further friction off of online transactions.

Nothing in its company or business history leaps out to suggest it fits the bill as a “threat to UK immigration control.” But that’s what the language of the Home Office’s correspondence asserts — and then indelibly inks in its final decision.

“I took them into a meeting room. And at that point, they hand me a bunch of documents and say: ‘We’re here to see and understand about your sponsored migrants.’ So at the beginning, the language is all very dehumanizing,” says Metail founder and CEO Tom Adeyoola, recounting the morning of the unannounced visit. “They hand me a bit of material which includes the sentence ‘you’ll be allowed a toilet break every two hours’. And I’m like, ‘am I being arrested?! What’s going on?’

“Then they ask ‘are your sponsored migrants here?’ I said I don’t know, I don’t manage them directly. I only had two.

“‘Can we see your lease? Can we see your accounts?’ Genuinely everything. ‘Can we see proof that this is your office?’ I was like, well you’re in the office… So [it was] very much a box-ticking exercise.

“And then the interview process going through with [the HR manager] was effectively ‘why have you hired sponsored migrants over the settled workers? Talk me through your process about how you track everybody in the organization?’

“‘What happens when they are not in one day? What happens when they’re not in at work the second day?’

“A bit of this thing was like an assumption that they’re not human beings but they’re like prisoners on the run.”

Image via Getty Images / franckreporter

Immediate effects

The January 31 decision letter, which TechCrunch has reviewed, shows how the Home Office is fast-tracking anti-immigrant outcomes. In a short paragraph, the Home Office says it considered and dismissed an alternative outcome — of downgrading, not revoking, the license and issuing an “action plan” to rectify issues identified during the audit. Instead, it said an immediate end to the license was appropriate due to the “seriousness” of the non-compliance with “sponsor duties”.

The decision focused on one of the two employees Metail had working on a Tier 2 visa, who we’ll call Alex (not their real name). In essence, Alex was a legal immigrant had worked their way into a mid-level promotion by learning on the job, as should happen regularly at any good early-stage startup. The Home Office, however, perceived the promotion to have been given to someone without proper qualifications, over potential native-born candidates. We detail the full saga over on Extra Crunch, along with the takeaways that other startups can learn from.

For Metail, the situation suddenly became about its own existence and not just the fate of one hardworking younger employee.

Metail’s other Tier 2 sponsor visa was for Dr. Yu Chen, who is originally from China, and leads the startup’s research efforts based at its Cambridge office. Chen has been with the business for around seven years — starting his relationship with Metail projects while still working on his computer vision PhD at Cambridge University.

Adeyoola describes him as “critical” to the business, a sentiment Chen confirms when we chat — albeit more modestly summing up his contribution as “quite theoretically involved in all these critical algorithms and key technologies developed by this organization since the very beginning”.

A major first concern for Adeyoola was what the loss of Metail’s sponsor license meant for Chen — and by extension Metail’s ability to continue business-critical research work.

The Home Office letter provided no guidance on specific knock-on impacts. And the lawyers Metail contacted for advice weren’t sure. “Our lawyers told us that that was the implication. In their revocation notice, they do not tell you what it means explicitly. You have to figure that out for yourself,” says Adeyoola. “Hence it is confusing and unclear.”

The lawyers advised Chen’s employment be suspended to keep the rest of the company safe — which instantly threw up further questions.

“Can I suspend his employment with pay or not with pay? Because the Home Office had his passport and they’ve had his passport since he’d applied for indefinite leave to remain in October and in January he still hadn’t had his passport back. He can’t go anywhere or do anything, so backward and forth it worked out that, yeah, we could suspend him with pay. But he couldn’t be seen at that time to be doing any work — and he’s critical for us.

“We had government R&D grants, he runs all our research — so I was like well we’re going to have to talk to the government and add an extension to that project.”

They had to tell everybody in the office that while Chen’s employment was suspended they weren’t allowed to talk to him. “He wasn’t allowed to use Slack,” Adeyoola recounts. “So if you were going to talk to him you had to meet him off-premise.”

“Nobody knows whether you can normally work,” says Chen of the uncertainty around his status at that point. “Are you just allowed to stay at home legally but not allowed to work? Lot of question marks. It’s a very, very rare scenario I think.”

Image via Getty Images / Dina Mariani

Adeyoola says he was also concerned whether Metail having its sponsor license suspended might negatively impact Chen’s in-train application for ‘indefinite leave to remain’ in the UK — which he had applied for in October, before the sponsor license suspension letter landed, having been in the UK the requisite ten years by then. And because, ironically enough, he had been “panicking” a bit about his future status as a result of Brexit.

Metail used an online email checking service, available via a Home Office portal, which suggested Chen could, in fact, work while the company license was suspended. At the same time Adeyoola had reached out to Chen’s local MP for help confirming his status — and with the aid of a political side-channel did manage to get it firmly confirmed in writing from the Home Office that Chen could still work while the license was suspended.

“We had to operate on lowest common denominator basis until we had written notice. Because systems operate on a ‘with prejudice’ basis,” says Adeyoola of the week Chen had been suspended from work.

“It was not in the letter. There was nothing in the letter about what it means for your people. Again, the human aspect of it seems to be the last thing on their mind. I think that’s part of the indoctrination of the people there — so they’re highly process-ified and trained so that they do their job.”

Chen’s period of suspension turned out to be mercifully brief, although that was purely due to lucky timing. Had he waited a month or so longer to lodge the original paperwork for his indefinite leave to remain, then his situation — and Metail’s — could have panned out very differently.

“In my case, I was just lucky because I started to apply for indefinite leave to remain before this stuff blew up,” he says, saying he filed the application around nine months before his Tier 2 visa was due to apply.

Nearly six months after filing for it in October, Chen’s indefinite leave to remain came through.

But by that time Metail’s sponsor license had gone. Now they wouldn’t be able to hire more people like Chen without overcoming major hurdles.

A hostile environment for immigration

Image via Toby Melville / WPA Pool / Getty Images

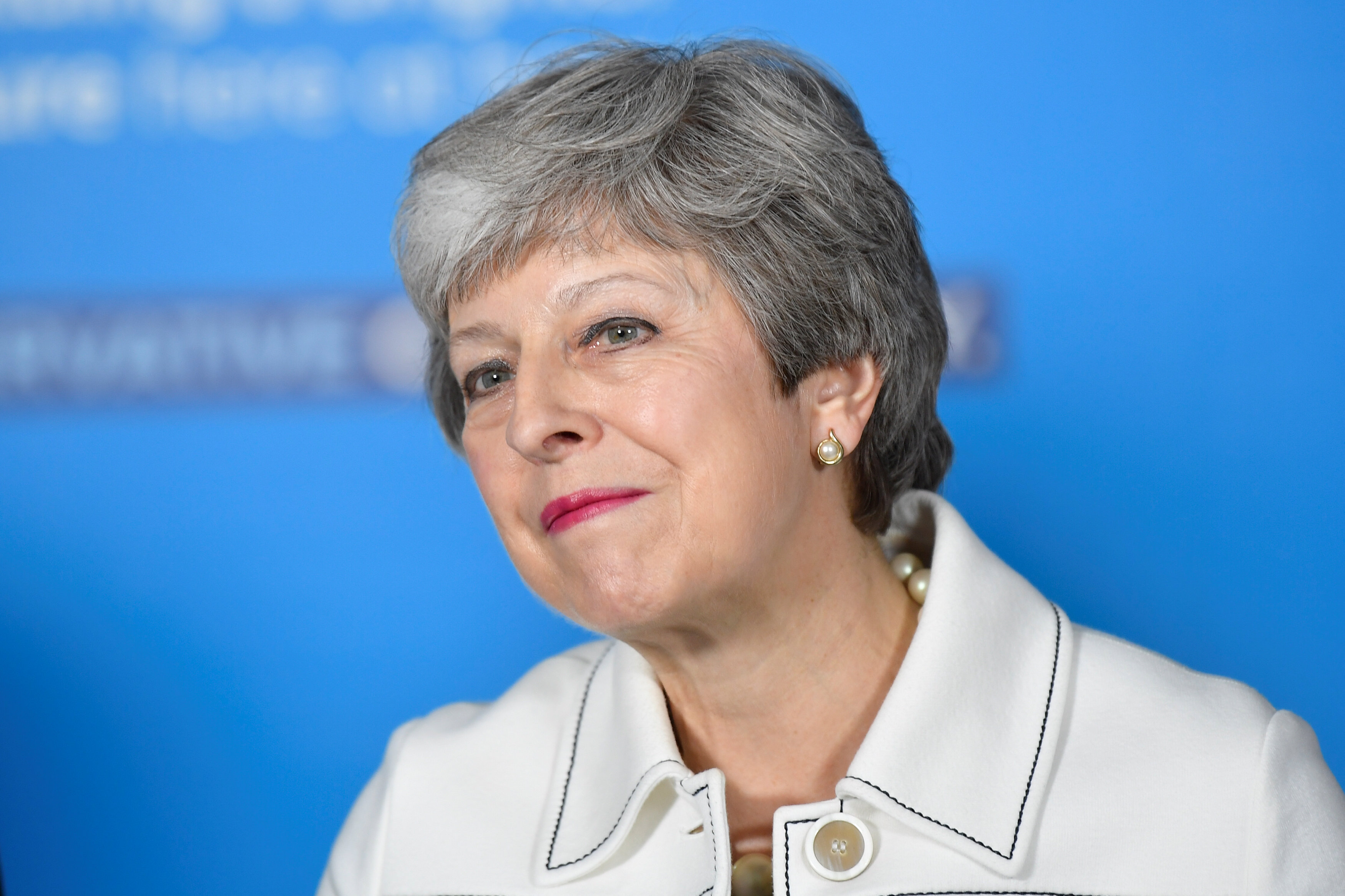

A photograph of the UK prime minister, Theresa May, smiles down at the reader of the Wikipedia page for the Home Office hostile environment policy.

As smiles go, it’s more rictus grin than welcoming sparkle. Which is appropriate because, as the page explains, the then-home secretary presided over the introduction of the current hostile environment, as the coalition government sought to deliver on a Conservative Party manifesto promise in 2010 to reduce net immigration to 1990 levels — aka “tens of thousands a year, not hundreds of thousands”.

The policy boils down to: deport first, hear appeals later. One infamous application of it during May’s tenure as home secretary saw vans driven around multicultural areas of London, bearing adverts with the slogan ‘Go Home’. The idea, criticized at the time as a racist dog-whistle, was to convince illegal workers to deport themselves by making them feel unwelcome.

Summarizing the broader policy intent in an interview with the Telegraph newspaper in early 2012, May told the right-leaning broadsheet: “The aim is to create here in Britain a really hostile environment for illegal migration.”

Associated measures introduced to further the hostile environment have included a requirement that landlords, employers, banks and the UK’s National Health Service carry out ID checks to determine whether a tenant, worker, customer or patient has a legal right to be in the UK, co-opting businesses and non-government entities into policing immigration via the medium of extra bureaucracy.

But in seeking to make life horribly difficult for workers who are in the UK without authorization, the government has also created a compliance nightmare for legal migration.

A Channel 4 TV report last year highlighted two cases of highly skilled Pakistani migrants who, after more than a decade in the UK had applied for indefinite leave to remain — only to be told they must leave instead. The Home Office cited small adjustments to their tax returns as grounds to order them out, apparently relying on a clause that allows it to remove people it decides to be of ‘bad character’.

That’s just the tip of the iceberg where the human impact of the Home Office’s hostile environment is concerned. There have been a number of major scandals related to the policy’s application. The most high profile touches Windrush generation migrants, who came to the UK between 1948 and the early 1970s — after the British Nationality Act gave citizens of UK colonies the right to settle in the country but without providing them with documentary evidence of their permanent right to remain.

The combination of thousands of legal but undocumented migrants — many originally from the Caribbean — and a Home Office instructed to take a hostile stance that pushes for deportations in order to shrink net migration has led to scores of settled UK citizens with a legal right to be in the country being pushed out or deported illegally by the government.

PHILIPPE HUGUEN/AFP/Getty Images

The Windrush scandal eventually claimed the scalp of May’s successor at the Home Office, Amber Rudd, who resigned as home secretary in April 2018 after being forced to admit to “inadvertently” misleading a parliamentary committee about targets for removing illegal immigrants.

Rudd had claimed the Home Office did not have such targets. That statement was contradicted by a letter she wrote to the prime minister that was obtained and published by The Guardian newspaper — in which she promised to oversee the forced or voluntary departure of 10% more people than May had during her time at the Home Office by switching resource away from crime-fighting to immigration enforcement programs.

May chose Sajid Javid to be Rudd’s replacement as home secretary. And while he has sought to distance himself from the hostile environment rhetoric — saying he prefers to talk about a “compliant environment” for immigration — the reality is the architect of the policy remains (for now) head of the government in which he serves.

Her government has not directly repeated the 2010 Conservative Party manifesto pledge to reduce net migration to the “tens of thousands”. But an immigration white paper published at the end of last year retraced the same rhetoric — talking about reducing “annual net migration to sustainable levels as set out in the Conservative party manifesto, rather than the hundreds of thousands we have consistently seen over the last two decades”.

It’s clear that controlling immigration remains right at the top of the government’s policy agenda, and is bearing out in how policies are enforced today.

Austerity and the Brexit divide

Image via Amer Ghazzal / Getty Images

As UK prime minister, May is also in charge of delivering Brexit. And here she has made ending freedom of movement for European Union citizens another immutable red-line of her approach — repeatedly claiming it’s necessary to ‘take back control’ of the UK’s borders to deliver on the Brexit vote.

Brexit — the UK’s 2016 referendum to exit the European Union — saw around 52% of those who cast a ballot voting to leave, or around 17.4 million people out of a total population of approximately 65.6M.

May’s interpretation of that result has been to claim citizens voted to end free movement of EU people and workers, despite there being no such specific detail on the ballot paper. (The referendum question simply asked whether the UK should remain a member of the European Union or leave.)

So her vision of a post-Brexit future will require UK businesses which want to recruit EU workers needing a sponsor license and relevant visas for all such hires. This will mean UK businesses hiring from outside the settled worker pool will have to expose more of their inner workings to the rules and regulations of the immigration system — with all the compliance cost and risk that entails.

From the outside looking in it might seem odd that the Conservative Party — a formidable political force that likes to claim it can be trusted to manage the economy, and which is traditionally associated with being more closely aligned with the interests of the private sector— is presiding over policies that drive up compliance bureaucracy for companies while simultaneously increasing their recruitment costs and squeezing their ability to access a broader talent pool.

But the traditional politics of right and left do seem to be in flux in the UK, as indeed they are elsewhere.

This is perhaps in part linked to the aging demographic of the Conservative Party’s base. (One disputed guesstimate, put out by a right-leaning think tank in 2017, suggested that the average age of a member of the party is 72; whatever the exact figure, no one disputes it skews old.)

The UK’s position in Europe — as a major economy, with a low unemployment rate and English as its first language — has also historically served to make the country an attractive destination for EU workers to settle. Hundreds of thousands of EU migrants arrived in the UK annually between mid 2014 to mid 2016, prior to the Brexit vote. Post-referendum, EU immigration dropped to 74,000 last year (even as net migration to the UK has not reduced).

That locus has long been a major benefit to UK businesses and startups, and so to the wider economy. But once it got geared into years of austerity politics — also introduced by the Conservative-led government in the wake of the 2008 financial crash — the country’s success as a worker and talent magnet started to butt up against and even drive rising resentment among sections of the population that have not felt any economic benefit from the concentrated wealth of high tech hubs like London.

Against a backdrop of growing inequality in UK society and sparser access to publicly funded resources, it has been all too easy for right-wing populists to re-channel resentment linked to government austerity cuts — framing immigration as a drain on services and pointing the finger of blame at migrants by encouraging the idea that they have a lesser claim than natural UK-born citizens to essential but now inadequately resourced public services.

This cynical scapegoating glosses over the fact that public services have been systematically and deliberately underfunded by austerity politics. But, at the same time, research that suggests EU migrants are in fact a net benefit to the UK economy has little comfort to offer those who feel economically excluded by default.

Image via Getty Images / Daniel Limpi / EyeEm

One interesting component of the UK’s Brexit vote split is that it appears to cut — not so much along traditional left/right political lines — but across educational divides, with research suggesting that pro-Brexit voters were more likely to live in areas with lower overall educational attainment.

High tech hubs and startup businesses are therefore in the awkward position of risking exacerbating the same sort of societal divide. They can be seen as driving the automation of traditional jobs, creating work that’s more specialized which in turn makes employable skills harder to attain from a low skills base, and concentrating opportunity and wealth in the hands of fewer people. Hence the needs of startups are becoming more difficult for politicians to prioritize.

There’s no doubt the politics of austerity has supercharged UK inequality as service cuts have hit hardest at the regional margins where wider economic gains were always the least profound and first to evaporate under pressure. While rising competition for scarcer state-funded resources has created perfect conditions for scapegoating migration.

A report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank earlier this month, at the launch of a five-year review into factors driving UK societal inequality, also warned that widening inequalities in pay, health and opportunities are undermining trust in democracy.

All of which makes responding to Brexit a political minefield for the UK government. The Brexit crisis seems to require a bold, society-wide re-engineering that attacks inequality of opportunity, radically invests in education, reskilling and upskilling to grow participation in the digital economy, and a tax policy that works to dilute concentrated wealth to ensure economic benefits are more fairly redistributed. None of which, it’s fair to say, is terrain traditionally associated with Conservative politics. (Though, in recent years, there have been attempts to claw in more tax from profit-shifting tech giants.)

Instead, the government’s top-line answer to the Brexit conundrum has, first and foremost, been to attack immigration. Playing to the lie that inequality is a simple numbers game based on population figures.

It’s not a strategy that properly addresses the question of how to manage wealth, resources and opportunity in an increasingly digital (and divided) world — to ensure it’s more equally and fairly distributed so that society as a whole benefits, rather than just a fabulously wealthy techno-elite getting richer.

Yet the government is badging its planned post-Brexit immigration reforms as a ‘Britain first’ overhaul that will create a system that’s “fair to working people here at home”, as the prime minister puts it. “It will mean we can reduce the number of people coming to this country, as we promised, and it will give British business an incentive to train our own young people,” runs her introduction to the immigration white paper published at the back end of last year, when Brexit was still marching towards a March 29 deadline.

The government making reducing net migration both flagship policy and political success metric has the knock-on effect of heaping cost, administrative burden and operational risk on UK startups — which rely, like all high tech businesses, on access to skills and talent to develop and scale commercial ideas.

Image via Getty Images / TwilightEye

But in the new austerity-fuelled Brexit political reality, the UK government not being overly supportive of the needs of talent-thirsty businesses seems to be the order of the day. Even as, on the other hand, other bits of opportune government rhetoric talk about Britain being “open for business” — or wanting the country to be the best place in the world to build a tech business.

Another government claim — that the planned “skills-based” future approach to immigration will allow businesses to cherry pick the very best talent from all over the globe — does not credibly stack up against the Conservative Party’s overarching push to shrink net migration.

The political reality, certainly for now, is that the ‘compliant’ environment approach to immigration is a euphemist label atop the same openly hostile policy that has slammed doors on people and businesses.

“I want to be able to hire great talented people with drive, enthusiasm and dynamism. I don’t want my choices to be restricted and if they are going to continue to be restricted we’ll have to look at other ways of maintaining the talent pool” says Adeyoola, discussing how he feels after Metail’s brush with the ‘compliant environment’.

“I’d love to just be able to hire the best person for the job… often a lot of that comes from people who want to come and make a life here. They have greater drive. So you get higher quality so you want to be able to hire those people if they come up.

“I think, unfortunately for us, we’re going to see fewer and fewer of them. Because if stuff continues the way it’s continuing, well we’ve already seen net migration from Europe fall dramatically over the last three years. In part that’s Brexit, in part that’s also because eastern European nations are flourishing… so the prospects are the other way. That’s just generally how things work. Great people move to great places.

”Just through going through this process it’s cost me money,” he adds of the audit and everything it triggered. “Real money in legal fees… lost time through weeks of work and effort from people inside the organization… We’re having to restrict the talent pool we can hire from… We’re going to have to spend more money on recruiters to find the right people… It is all just negative… The Brexit argument has always been Brexit will mean fewer EU which means we can have more people from outside… Well, that’s not how the immigration rules work now.

“You’re trying desperately to keep people from outside out. So I can’t believe that, post-Brexit you’re going to loosen the rules… So this whole thing about ‘fewer EU, more commonwealth and more everywhere else’ is not believable.”

Towards politically charged borders

Image via Nicolas Economou/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Change is coming for the UK’s immigration system. But if the government executes on May’s version of Brexit — which intends to end freedom of movement for EU citizens — it will require UK businesses to interface with the Home Office if they wish to recruit almost any skilled individual from overseas.

Simply put, the same set of rules will apply to EU and non-EU migrants in the future. With the caveat that it remains possible for any post-Brexit trade deals that the UK might ink to include agreements with certain countries to carve out distinct offers related to work visas.

Per its white paper, the government has said it will simplify immigration requirements, as part of the shift to a single, “skills-based future immigration system” post-Brexit, slated from 2021 onwards.

Planned changes include removing the cap on skilled workers, which has — in years past — put another hard limit on startups hiring skilled migrants as, up until doctors and nurses were excluded from the quota last summer, it kept getting hit each month — limiting how many visas were available to businesses.

The government has also said it will do away with the requirement that employers advertise jobs to settled workers. So no more resident labour market test — aka the process which helped skewer Metail’s sponsor license.

Instead, for skilled workers, the plan is to apply a minimum salary threshold of £30,000 (including those with lower, intermediate level skills than now) — using pay as a lever to discourage migrant workers from being used to undercut wages. So no more forcing businesses to undertake an arduous, lengthy and risky (from a compliance point of view) process of advertising to settled workers in case one can be found for a vacancy.

Although the 2021 timeline for introducing the skills-based system that’s written into the immigration policy paper was contingent on the UK leaving the EU on March 29 this year. Whereas Brexit still has yet to happen. So the implementation date for any post-Brexit immigration reforms remains as equally uncertain and moveable a ‘feast’ as Brexit itself.

“Cost certainly won’t go away,” says Charlie Pring, a senior counsel who specializes in immigration work for law firm Taylor Wessing, of the planned reforms. “The red tape will go away a little bit from 2021 when they rework this new one-size fits all system that will cover Europeans and non-Europeans — because they’re going to scrap the cap and they’re going to scrap advertising. And they’re also going to lower the skill level as well — so almost like A-level qualified jobs rather than graduate one jobs. So it’ll be mid-level jobs as well as graduate ones. But that’s still best part of two years away — so until then employers have got to lump it.”

The immigration system that remains in force has been designed to make the process of sponsoring migrant workers akin to a tax on businesses — with associated cost, complexity and uncertainty designed to discourage recruitment of non-UK workers.

PAUL FAITH/AFP/Getty Images

For startups, Pring (who to be clear did not advise Metail) sees costs as the biggest challenge — “because the visa fees are so high”. He also points out the fees scale with the company. Once a startup is “no longer deemed to be a small” by the Home Office there’s “a higher skills tax to the government as well. So that’s a real issue”.

Startups don’t get any kind of compliance break based on the fact they’re trying to be innovative, develop new skills, tap novel technologies and create new business models. The same skeptical compliance can also be seen operating across the board — whether a business entails low tech seasonal fruit picking or is a high growth potential AI startup with a wealth of PhD expertise and patented technologies.

Nor does the Home Office have any remit to actively support sponsors to help them understand how to fulfil all the various knotted requirements of an immigration system that can be charitably described as opaque and confusing.

On the contrary, the government’s goal of shrinking annual migration creates a political counter-incentive for immigration rules to be complex and unclear. Encouraging enforcement to be aggressive and confrontational — and for compliance officers to hunt for reasons to find and penalize failure.

UK startups that sponsor migrants should understand they remain at risk of falling foul of the charged politics swirling around immigration — and having all their sponsored visas liquidated and business penalized by a system that, parts of which the government’s own policy plan concedes are not working as intended.

Even with reform looming, the future for entrepreneurs in the UK looks no less uncertain — if, as the government intends, free access to the EU talent pool goes away after Brexit. That will give the Home Office far greater control over migration, and therefore a much bigger say over who businesses can and cannot hire — putting its hands on cost and skill levers which can be used to control migrant flow.

Here’s Pring again: “The government is deliberately funneling people through into Tier 2 [visas]. If they push everybody through Tier 2, which is what they want, that’s the way they control skill level and salary level because you can only get a Tier 2 visa if the job is skilled enough and you’re paying enough for it. So it enables the government to put an element of control onto the visa numbers. And even though they’re not [generally] capping the numbers… they are through the backdoor deterring people from applying by making it difficult to qualify and ramping up the visa fees.”

The UK’s future immigration system is also being fashioned by a Conservative government that sees itself under siege from populist, anti-immigration forces, and is led — at least for now — by a prime minister famed for her frosty welcome for migrants.

Without a radical change of government and/or political direction it’s hard to imagine those levers being flipped in a more startup-friendly direction.

Entrepreneurs in the UK should therefore be forgiven for feeling they have little reason to smile and plenty to worry about. Rising costs for accessing talent and growing political risk is certainly not the kind of scale they love to dream of.

from TechCrunch https://tcrn.ch/2HppDHl

No comments:

Post a Comment