When Karen Leibowitz and Anthony Myint opened The Perennial, the most ambitious and expensive restaurant of their careers, it was essentially on a self-dare. The married duo had found enormous success with their previous restaurant in San Francisco, Mission Chinese Food, but realized something was missing. “Basically zero chefs were working on climate change,” Myint told me recently. The food system is among Earth’s worst polluters, contributing more greenhouse gases than cars, planes, and ships combined. But action from the industry had, up to that point, been uninspiring at best.

So when a local developer offered them a new space, they jumped at the opportunity to do something a little wild: build a completely carbon-neutral restaurant. Their “laboratory of environmentalism in the food world” opened to downtown diners in January 2016.

Myint was the crazy-ideas guy and Leibowitz the shrewd marketing whiz, and between them no part of the restaurant escaped eco-proofing. The floor tiles were recycled, the cocktails on tap to save ice, the kitchen’s ventilation hood laser-activated. There was a “live pantry” herb wall. Diners ate the first bread baked with Kernza, the trade name for a perennial grain developed by Kansas’s Land Institute. Paper menus were composted and fed to worms, which were dehydrated and fed to fish, whose ammonia-rich waste fertilized the lettuces, guava plants, curry leaves, and edible flowers used in the kitchen.

The pièce de résistance was serving meat with a dramatically lower carbon footprint than normal. Every pound of beef produced today by modern farming generates, on average, the equivalent of 22 pounds of carbon dioxide (known as CO2e). Thanks to ranching techniques used by The Perennial’s suppliers, one pound of beef is offset by 45 pounds of carbon sequestered in the soil. It was enough for a steak to cancel its own footprint, and then do the same for the beef tacos at a restaurant down the street.

Their trick was carbon farming. Myint and Leibowitz had linked up with a ranch in nearby Marin County, one of a handful in a pilot project in California pioneering a method that is said to dramatically reduce emissions.

Between machinery, fertilizer, and animal waste, modern agriculture is a horrible carbon emitter. But so-called carbon farms practice techniques like managed grazing, compost applications, and cover crops that deliberately draw carbon into the topsoil. This not only keeps the carbon out of the atmosphere but aims to naturally enrich the soil, ideally yielding healthy food that tastes better. Not everybody agrees that this kind of regenerative farming can make a dramatic difference in overall emissions, but many leading scientists have gotten excited by the possibility that it could help turn agriculture from a major climate problem into, perhaps, part of the solution.

The discovery convinced Myint and Leibovitz they were on to something much bigger—and that the easiest, most practical way to tackle global warming might be through food. “We were like, ‘Wait, you can convert greenhouse gases into healthy soil with a few simple changes to farming?’” Leibowitz says. “‘Why is no one talking about this?’”

But they also realized that what has been called the “country’s most sustainable restaurant” couldn’t fix the broken food system by itself.

So in early 2019, they dared themselves to do something else that nobody expected. They shut The Perennial down.

‘The most optimistic story in food‘

Freed from running a restaurant, Myint and Leibowitz began spreading the gospel of a carbon-negative food system full time. “It’s the biggest, most optimistic story in food,” he announced the first time we talked about it, last summer. The energy they had put into The Perennial was reinvested in projects including Zero Foodprint, or ZFP, which focuses on carbon-farming projects, and shares carbon-reduction tools pioneered by The Perennial with other restaurants. Audits can also identify partner restaurants’ emissions, which those restaurants work to eliminate, and whatever remains is countered by purchasing offsets. By the time The Perennial closed, in February 2019, it had recruited fine dining peers like Copenhagen’s famed noma and Berkeley’s legendary Chez Panisse.

Since then, the organization, with Leibowitz as executive director and Myint as director of partnerships, has flourished. An initial handful of fine-dining partners has climbed to over 100 active and pledged members. And when it comes to the cost of offsets, a pattern has emerged. “In almost every case,” Myint says, “1% of revenue was as much as or more than it would take for the restaurant to be carbon neutral.”

It was a modest enough number, but restaurants are cash-strapped at the best of times. Zero Foodprint ended up suggesting a voluntary 1% surcharge on bills, just a few cents per diner, which can go to farmers to help them implement healthy-soil projects.

The recognition arrived quickly. Myint was the first American to win the Basque Culinary World Prize last summer, a prestigious €100,000 award given to the chef who has made the year’s greatest social impact through food. And then, in March 2020, Zero Foodprint won the James Beard Foundation’s Humanitarian Award.

Yet—just as with The Perennial—it wasn’t enough. Despite their success, Leibowitz and Myint realized they could recruit all the best restaurants on the planet and it would barely budge Earth’s 40 billion tons of annual carbon dioxide emissions “It’s 1% of restaurants buying from 1% of farms,” Myint admits.

But what if it wasn’t just fine dining restaurants? If Noma’s or Chez Panisse’s surcharge can help sequester 100 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, what could 1% of the $3 trillion global restaurant industry do? And why stop at restaurants? What if corporations that operate their own cafeterias joined in? What if there was buy-in from food brands, caterers, hotels, grocery chains, and agricultural giants?

Impossible burden

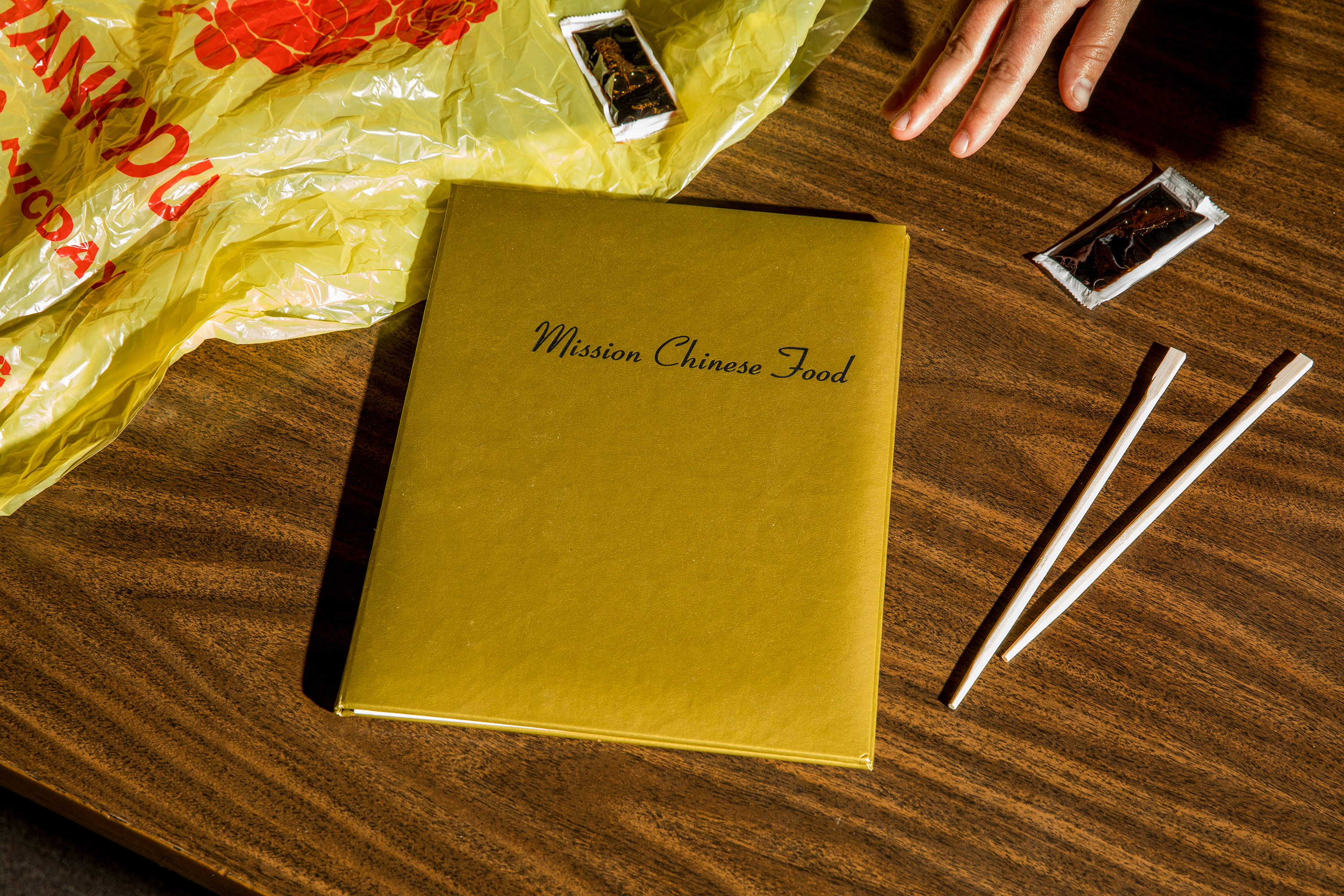

The couple have come a long way from where they started. In 2008, Myint was a line cook at Bar Tartine when he started selling $5 “PB&Js”—pork belly and jicama flatbreads—from a taco cart he and Leibowitz had borrowed on a lark. Soon, with a loyal crowd of fans, the operation migrated to a dingy Chinese takeout joint and helped pioneer the idea of pop-up restaurants. By 2012 Leibovitz’s book Mission Street Food was a bestseller, and the New York outpost of their second restaurant, Mission Chinese Food, commanded three-hour lines every night.

But Leibowitz says it was the birth of their daughter that year that inspired them to blow up the conventional restaurant mold again in order to pursue radical sustainability. They couldn’t help but wonder, “What type of world are we leaving to Aviva?”

The next year, Myint formed Zero Foodprint with the food journalist Chris Ying and a Fortune 500 sustainability consultant named Peter Freed. As Myint and Leibowitz began researching carbon reduction for the Perennial, they became fascinated with the possibilities of farming, and with the work of one particular rancher: John Wick, carbon farming’s unofficial founding father and cofounder of the Marin Carbon Project.

At that meeting, Wick declared that Zero Foodprint’s work offsetting restaurant greenhouse gases “wasn’t thinking big enough.” With carbon dioxide levels at 417 parts per million and rising—their highest since the Pliocene period 3 million years ago—it wasn’t enough to simply not pollute the air. They needed to be actively removing atmospheric carbon, Wick said.

He laid out how, basically by accident, he’d identified a very productive way of doing that: add compost, a biologically stable form of carbon, to jump-start the process, alongside managed cattle grazing, which mimics the habits of migratory herds, and perennial grasses—deep-rooted plants that, unlike annual crops, don’t expose carbon to oxygen every time they’re tilled. Their exact benefit is a hot debate among soil scientists, but Myint and Leibowitz were instant converts: they named their new restaurant The Perennial on the drive home. Wick eventually introduced the couple to one of the local regenerative farms, Stemple Creek Ranch (which produced the beef they later served diners), and joined the Perennial Farming Initiative’s board of directors.

In February, before the pandemic, I met Wick for ice cream at Myint’s insistence. We were in Marin County’s Mill Valley, a small town just north of the Golden Gate Bridge, while his wife, the children’s author Peggy Rathmann, was in town running an errand He explained how in the late ’90s they had bought a “piece of wilderness”—540 acres in nearby Nicasio. In 2003, an ecologist they hired, Jeff Creque, persuaded them to reintroduce livestock. Within five weeks the native grasses flourished once again, and the 250 cows gained 50,000 pounds of extra weight. It made Wick curious what was happening down in the dirt.

He brought in UC Berkeley biogeochemist Whendee Silver, an expert on soil’s climate impacts, to analyze the soil at several dozen Marin ranches. Those that were spraying manure ended up having much more carbon in their soil, which showed how agricultural practices could make a difference—even if it wasn’t the best path to follow overall (manure spraying generates lots of carbon emissions.) After further investigation, they realized that using compost, and the other regenerative techniques, could also lock carbon into the ground without the same costs.

In fact new data from a decade-long analysis of Sierra foothills rangeland, shows that those sites sequestered an additional ton of carbon dioxide every year for 10 years without any extra help. “The soil system pulled down the carbon and integrated that energy, which held more water and promoted more plant growth, which resulted in more carbon being removed, which held more water, which promoted more plant growth—it’s a self-feeding phenomenon,” says Wick. “And when we scale it, we can actually lower the temperature of the planet.”

To champion these practices, Wick, Silver, and Creque formed the Marin Carbon Project, which has since grown into arguably the world’s foremost center for research on soil carbon and regenerative farming.

Silver’s most recent paper on soil’s drawdown potential predicts that agricultural sequestration can lower global temperatures by 0.26 °C before 2100 (the Paris climate agreement has a target of 1.5 °C.) An agricultural think tank, the Rodale Institute, goes even further: more than 100% of Earth’s current annual carbon emissions could be captured, it estimates, by switching to these inexpensive, widely available farming practices.

For those who are optimistic about carbon farming, the numbers tell an intoxicating story. Stemple Creek, for example, uses techniques on its entire ranch to offset beef emissions. According to Myint’s math, the benefit achieved over a five-year period from one compost application was the equivalent of not burning more than 1 million gallons of gasoline. The measurements have their skeptics, but the reason for enthusiasm is obvious. Think about the vast, concentrated animal feeding operations that supply Walmart, McDonald’s, and Tyson.

Not everybody is so bullish, though. Critics worry that in a warming world where smoke now obscures the sun, pressure to act quickly is advancing a cause faster than science can keep up. Tim Searchinger, a scholar at the World Resources Institute, argues that data is lacking. Ronald Amundson, a biogeochemist whose office is next door to Silver’s at Berkeley, says the proposal is “overly optimistic,” and the method itself has too many variables.

A big problem is execution. For farms to adopt climate-friendly practices, they need restaurants that reward them for doing so. But even before the pandemic laid waste to the food industry, chefs had been operating with razor-thin profit margins and, oftentimes, maybe a week’s worth of money on hand. “Farmers are in the same boat,” says Zero Foodprint’s program director, Tiffany Nurrenbern. “The burden of solving this problem ultimately falls on two of the least equipped groups to deal with it.”

That’s where Zero Foodprint steps in. It audits a restaurant’s emissions, and then helps set up systems where diners pay a few cents to fund farming grants. ZFP then shepherds the money to farmers who need investment to adopt regenerative farming practices, improving the system one meal at a time.

New rules of business

When he accepted the Basque prize last summer, Myint made it clear that he felt ill equipped to lead a revolution. “I started in kitchens to avoid talking with people,” he told the audience, which included dozens of food-world dignitaries. “So this is very ironic.”

Yet the impending climate cataclysm has made a salesman of the introverted chef. Now, he and Leibowitz spend their days discussing soil organic-matter levels with multinational food brands and trying to convert Silicon Valley tech firms to the zero-carbon agenda. Before the pandemic, Square, Salesforce, Stripe, and Google’s food-truck vendor Off the Grid committed to joining, and by now they’ve finished converting their food programs to zero carbon or are in the process of doing so.

The aim is to cause a domino effect that disrupts the global food-supply chain. To avert catastrophic climate change, it’s understood we must reach drawdown, a point at which the planet’s greenhouse-gas concentrations start declining for the first time since the Industrial Age. That will require mitigating gigatons of emissions. Project Drawdown, the most highly publicized report on how to make it happen, identifies 100 pathways that—for a total cost of $27 trillion—could get us to this milestone by 2050 if adopted together. Forty percent of these solutions involve food, agriculture, or land use.

Last year, Americans spent $1.7 trillion on food and beverages. For them to pay an additional 1%, Myint says, is “virtually negligible” and would contribute dramatically to costs. In the case of corporate partners, asking businesses to give 1/100th of their earnings isn’t a losing philanthropic strategy, either: One for the World, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard’s 1% for the Planet, and Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff’s Pledge 1% have thousands of corporate members that have committed billions of dollars. Drawdown’s $27 trillion figure also happens to equal around 1% of the gross world product. Myint concludes, “We just need to have a new business-as-usual where 1% goes toward solutions.”

Investors are starting to see a business opportunity. In January, Starbucks outlined a plan to become “resource positive,” vowing to invest in regenerative farming. Burger King just debuted a low-methane beef patty. General Mills is using Kernza to push a carbon reduction program. Last summer, a Boston-based startup called Indigo Agriculture launched an initiative aiming to remove 1 trillion tons of carbon from the atmosphere through regenerative farming; 18 million acres are enrolled so far. Al Gore told a conference earlier this year that carbon farming is “one of the most promising and biggest solutions to the climate crisis,” and he has embraced it on his 400-acre Tennessee farm. A big consortium that includes Indigo Ag has already raised over $20 million to build a marketplace to sell soil-carbon credits.

Some already see a market bubble forming. Project Drawdown cofounder Jonathan Foley recently told Mother Jones he’s worried they’ve started veering toward a “Silicon Valley hype cycle,” that predictable sequence where tech invades a field and announces plans to disrupt it, but before long “everybody realizes, ‘Oh my god, this is overhyped, and it’s not going to deliver.’”

You can hear Wick’s frustration emerge over the frothiness around all of this. The Marin Carbon Project’s approach is painstakingly data-driven—Wick loves the mnemonic “Measure, map, model, and monitor to manage.” Lost in the hype, he told me, is that not until “you measure every form of carbon in and out of the system” can you know if what you’re doing is even good or bad—“But nobody wants to hear that.”

Zero Foodprint offers tools for more precision, he says. It gives farmers grants to improve their technical skills and get access to experts who teach the methodology. “Anthony is a genius,” he told me. “He created two really compelling pathways with entry points for restaurants and patrons to actively participate in something that is science-based, government-supported, and rolling out right now, in real time.”

But back on the corporate side, Zero Foodprint elicits a mixed response. There have been talks with big restaurant chains and tech companies, and successes such as the agreements with Salesforce and Square. But others have shrugged Myint off, while some have been harder to pin down. Last year, one of Zero Foodprint’s highest-profile member farms, Markegard Family Grass-Fed, took part in a pilot to supplying negative-carbon beef to Google’s downtown San Francisco offices, whose cafeterias feed 7,000 employees per day. “People loved that there was a story behind it,” recalls co-owner Doniga Markegard. But the project lasted just four weeks, and Google now says employees will not be asked to return to the office until at least the summer of 2021.

All this has forced Myint to reconsider his plans to tackle corporate food programs as the next domino. Today, the collaboration he seems most excited about isn’t with a billion-dollar corporation. It’s with the country itself.

“A giant crowdfunding operation”

Zero Foodprint believes it can build up a war chest that will—in theory, anyway—fund all the carbon farming there’s demand for. That plan begins locally with California, which is how I ended up in the Mission District shortly before the covid-19 lockdown went into effect, in the packed showroom of Bernal Cutlery, a lauded local knife store. Restaurateurs and state environmental policymakers were slurping oysters left over from a live shucking contest, while the rest of us battled for free beer tokens in a climate-trivia game. It was a launch party for Restore California, the state’s new healthy-soil initiative, part of Governor Gavin Newsom’s drive to be carbon neutral by 2045. The first program of its kind in the US, it pools every 1% surcharge collected by partners statewide and uses the money to fund regenerative agriculture on California farms.

Halfway through the evening, Leibowitz climbed onto a chair below a wall of very large knives. As industry newbies, she said, they quickly learned a “very sobering” fact: that as much as half of greenhouse-gas emissions are related to the food system. “The amazing news,” she added, “is there are ways to cultivate food that draw down these gases. But it takes money for farmers to make those changes. So we’ve basically conceived of a giant crowdfunding operation to direct money into climate solutions.”

Myint, who had popped up on an adjacent chair, likened the idea to renewable-energy surcharges, where utility companies charge customers $5 a month to improve the electric grid all at once. “In a couple of years, they’re up to 100% renewable energy, and that rapid change would never happen without that system in place,” he said. “Restore California is the same system, only partners charge an extra 1% and use it to improve the food-farming grid.”

Mission Chinese’s surcharge alone had already generated over $50,000. That night Myint told the crowd that one local dairy farm was receiving a $25,000 grant that could potentially take 100 tons of carbon out of the atmosphere each year.

But California diners aren’t auto-enrolled in Restore California the way they are in the energy surcharge program. Zero Foodprint has tried cementing partnerships with local governments statewide to bridge that gap. Discussions with Sonoma County began in December; the two local conservation districts there already have 18 carbon-farm plans in place, “so there’s essentially already a landing pad for the funds to go into immediate action,” Myint says. While ongoing talks with Sonoma and other counties have been paused in light of the pandemic, Boulder County in Colorado has just launched a program in partnership with Zero Foodprint modeled on Restore California. Called Restore Colorado, and spinning itself as “table-to-farm,” the project received one of the first of the USDA’s new compost-and-conservation grants.

Whatever happens, Myint and Leibowitz’s interest in regenerative agriculture was, like most things with them, ahead of its time. Peter Freed, one of Zero Foodprint’s cofounders, says he could see the gears clicking in Myint’s head as the chef digested spreadsheet after spreadsheet assessing Mission Chinese Food’s climate footprint.

“It just became something he grew more and more passionate about,” Freed told me. “The question when we launched Zero Foodprint was ‘Will the environmental industry come around to embrace regenerative agriculture as an important piece of the puzzle?’ If you had given Anthony his dream, it would have been that on day one.”

Any progress that does happen, of course, must now occur against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which has devastated the restaurant industry. New data just released by the National Restaurant Association shows that one-sixth of US restaurants have closed. Forty percent claim they can’t last another six months without government aid, and it will be an arduous road to recovery for the rest. One of the latest victims is the New York outpost of Mission Chinese: Danny Bowien, who cofounded it with Myint and Leibowitz and was its chef and owner, recently announced that it will close permanently at the end of September.

But perhaps covid-19 was the perfect catalyst for change. After California’s lockdown began, I asked Myint how they would handle this step backward. He said these were uncharted waters for restaurateurs, but scary situations do have one upside: “There’s no fear of change.” Zero Foodprint has added five partners since August and is about to welcome a new group of restaurants in Denver. “The industry is starting from scratch,” Myint says. “People are ready to become part of this solution moving forward.”

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/2EsVSXy

No comments:

Post a Comment